FeatureThe Complete History Of Laurent Ferrier

Everything you need to know about the Laurent Ferrier—the man, the brand and the timepieces that follow the highest standards of haute horlogerie

May We Recommend

When discussing Laurent Ferrier, I am brought to mind of Marcel Proust for a vividly evocative reason. According to the French novelist’s statement, “Style… is a revelation of a private universe which each one of us sees but which is not seen by others.” Deep inside Laurent Ferrier’s imagination, inchoate but present when he made his first pocket watch in 1968 and enriching itself to full maturity over his 37 years in a famous watchmaking maison, was a singular voice of immeasurable horological grace. When he did unveil this vision to the world with the launch of his eponymous brand in 2009, the watch that he created, the Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral, meaning double balance spring, triggered an incredible flood of what Proust would call ‘involuntary memories’. Ferrier reconnected us all with the love for classical watchmaking, a remembrance of things past, that we had almost forgotten. But now, thanks to him, it came flooding back to us more powerfully than ever. Laurent Ferrier would become our bridge between the past and the present. His watches are the living, beating repository of horology’s greatest collective memories. So artfully did he wield nuanced details inspired by 19th and mid-20th century Swiss watchmaking that his vision felt like it had already existed for a century or more, already permanently inscribed into the lexicon of horology’s great canon.

Even more importantly, at a time when watchmaking was becoming bombastic and theatrical, he reintroduced the world to the type of watchmaking that was serene. Says Ferrier, “In art, a baroque period is always followed by an era of renewed classicism. That is the type of watchmaking I wanted to reintroduce to the world. Classic watchmaking as I loved it.” Which is to say watchmaking that is devoid of hyperbole. An ethos of smooth curvilinear forms inspired by the touch of the divine in nature. Watchmaking that champions restrained beauty belied by technical prowess that instantly made Laurent Ferrier one of the most compelling high watchmaking maisons around. In his humility, Ferrier demurs, “We are hardly a maison. We are just a small enterprise that makes just around 150 watches a year.” Yet, the emotional impact of Laurent Ferrier far exceeds the quantities of watches he creates.

I have witnessed grown men, sagacious and learned, lost in rapture in the microcosmic depths of the Tourbillon Double Spiral. Its ethereal movement architecture and its visual symphony of hand-finished details trigger memories of past horological loves like a poem by Pablo Neruda. I have seen jaded weary collectors smile in childlike delight at the delicate hue of Ferrier’s chemin de fer on his grand feu enamel dials or revel in the dynamic tension presented by the smooth pebble-like form of his École case contrasted by its virile Officer’s lugs. I, myself have been immutably seduced by the Constantin Brâncus’i-like linear attenuation of his Assegai hands. Each Laurent Ferrier watch is part of a multi-level codex. As you examine it, you unearth layer after layer of detail that is the product of the watchmaker’s internal reflection and quiet consideration. All of which combine to create his horological intellect, many elements of which were taught to him years before he dreamed of creating his own brand.

The Galet Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral was chronometer-certified by the Besançon Observatory. The calibre used within had an original device used in the tourbillon escapement, with double inverted hairsprings that kept the balance centred on its axis. This system guaranteed extreme reliability of the regulating system

The Story Of Laurent Ferrier, The Man

Ferrier explains, “I grew up around watchmaking, so there was always a sense of predestination that I would work in watches. I imagine in the same way that it was for my son, Christian. My father was a specialist in grand complications and I was infected by his passion in particular early on. He would tell me stories of how timekeeping was interlinked with the story of human history. That the marine chronometer was the instrument which allowed man to safely navigate the seas.” But at an early age, Ferrier was also swept up by a passion for auto racing. Which he feels added to his interest in watchmaking in a unique way. He explains, “I started in local races but soon gravitated to endurance racing. I loved the idea of trying to achieve perfection and consistency with each lap. I suppose this is also one of the things that drew me to horology; the idea of trying to express something perfectly. Racing taught me a lot about details. If your car is not prepared correctly, if you are not mentally focused, if you do not enter each turn at the right speed or the correct angle, it effects the outcome.”

For Ferrier, the mental discipline, the rigor of character, the focus necessary to be a great driver was similar to his approach to watchmaking. He says, “Similarly in watches, every single element makes a critical difference in the outcome. This is something that I have tried to apply to Laurent Ferrier watches. Ours is a design language that is restrained, some might even say minimalist, but if you look at the details, the colour density of the font for each marker, the shape of the crown, the compound curve of the sapphire crystal, every element has been painstakingly considered over and over until we thought it was perfect.” In addition, Ferrier would quickly understand that both racing and watchmaking involved every one of the human senses—a revelation that would serve him well in life. He explains, “When I was young, my father would encourage me to touch and feel the watches he worked on to start to develop a sensitivity to their tactility. It is similar to driving; you see with your eyes but you control the car through feel that comes from the wheel to your fingertips, and the interaction of the car with your body through the seat.”

As Ferrier explains, the sense of his family’s horological predestination led him to watchmaking school where he excelled graduating at the top of his class. But even at an early age, Ferrier had a very distinct perception of what style of watchmaking he loved. He states, “When I was 16 years old, I completed my watchmaking studies and presented my Montre d’École in 1968, which was an attempt to create a very elegant and pure expression of watchmaking. The next 40 years would be a period where I would learn and define the codes of my vision for watchmaking. I would come to love apparent simplicity or purity in design combined with extremely ambitious technical innovation. What I love is the dynamic tension between a watch that is wonderfully restrained and charmingly understated when you look at it from the front, but as you examine the details and then turn it over to look at the movement, you suddenly become aware of how complex it is.”

It would be impossible to fully understand Laurent Ferrier without discussing his time at Patek Philippe. Says Ferrier; “I owe a tremendous amount to my time spent at Patek Philippe. For 37 years, I only worked at one watch brand and I can say unequivocally that it is an incredible maison. Their tradition was to always take on board the top one or two graduates from the watchmaking school and as I was fortunate enough to do well, they recruited me. My first job was to work on a project related to a quartz digital display chronograph which had finally been abandoned. This left an impression on me; that human beings still respond to traditional time telling in a very fundamental way. It would really reinforce a belief in mechanical watchmaking for me even when the ‘quartz crisis’ started. I recognised that all electronic devices eventually become obsolete. Whereas my father might be working on a watch that had been left dormant for many years, but with some oiling and service, it would start immediately and keep time as perfectly as when they were new.”

Amusingly, his passion for racing caused a brief departure from watchmaking, but its call to Ferrier was ultimately too beckoning. Eventually his two passions found a healthy compromise thanks to a kind boss. He explains, “My boss was very kind to me so, by 1971, I started by working in all the different departments at Patek Philippe. But I was really catching the auto-racing bug at this time. So I left for another job in the auto industry but really because it would afford me the flexibility to race. If you are going to compete on the weekend, then you need all of Friday to prepare your car and learn the track. And all of Monday to debrief, and for repairs and maintenance. Eventually my boss at Patek asked me if I would be willing to come back. I was very happy to but asked if I could apply my holiday leave such that I could take each Friday off during the racing season to prepare my car. As soon after the ‘quartz crisis’ hit the industry, my work week was shortened to four which was perfect for me.”

But even as his racing career flourished, his adventure in watchmaking also offered new opportunities. Says Ferrier, “In 1974, I ended up in the department that oversees the development for all the external parts of the watch. Meaning that when Philippe Stern decided on a new watch, the movement would be developed by another team, while our team would create everything that ‘touched the air’ or that was external, specifically the case, the dial and hands, the crystal and the bracelet. This was an incredible job because you really understand how the smallest detail, how the hands are bent to follow the curve of the crystal, the thickness of lugs, the size of the crown, of the pushers, the integration of the bracelet—all of these things made such a huge difference.”

One of Ferrier’s first projects was a watch that would become one of horology’s most recognisable icons, an iconoclastic design for an integrated-bracelet steel watch created by Gérald Genta. Says Ferrier, “I was lucky enough to be part of the project that developed the Nautilus. We received the plans from Genta’s atelier and the instructions from the great Philippe Stern to make these two-dimensional drawings a reality. What is funny is that because this was far before the era of three-dimensional digital modelling, the front of the watch was always drawn perfectly, as was the back of the watch, but the side was often left as something for us to interpret. The brilliance of this design was the dramatic contrast between the oversized 39mm incredibly modern case, contrasted by the thinness of its profile at just 7.6mm. The Nautilus is a two-part interlocking and overlapping case that is held together by special screws that travel through the vertical axis of the case’s ears. When we were finished, we thought it was one of the most beautiful and original watches we had ever seen.”

A Partnership Born In Racing

Ferrier’s early life began to find its rhythm and with success in both racing and watchmaking, he found himself content. What he didn’t realize was that a friendship would lead him both to a podium position at the 1979 24 Hours of Le Mans as well as the creation of his own brand. He explains, “Throughout this time I began racing quite competitively. Eventually starting in 1975, I began competing at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. That is how I met the man that is now my business partner, as President and main shareholder, in Laurent Ferrier watches, François Servanin. He was a very interesting man. He had already established a reputation for helping to develop race engines and he was a rising driver on the endurance-racing scene. At Le Mans in 1978, François came in 11th overall and first in the grand touring category driving a Porsche 911. That same year I came in 10th overall and first place in the under-two-litre prototype category in a Chevron ROC. Based on our friendship and our mutual respect for one another, we decided to race in a Kremer-prepared Porsche 935 in 1979 where we placed third overall.”

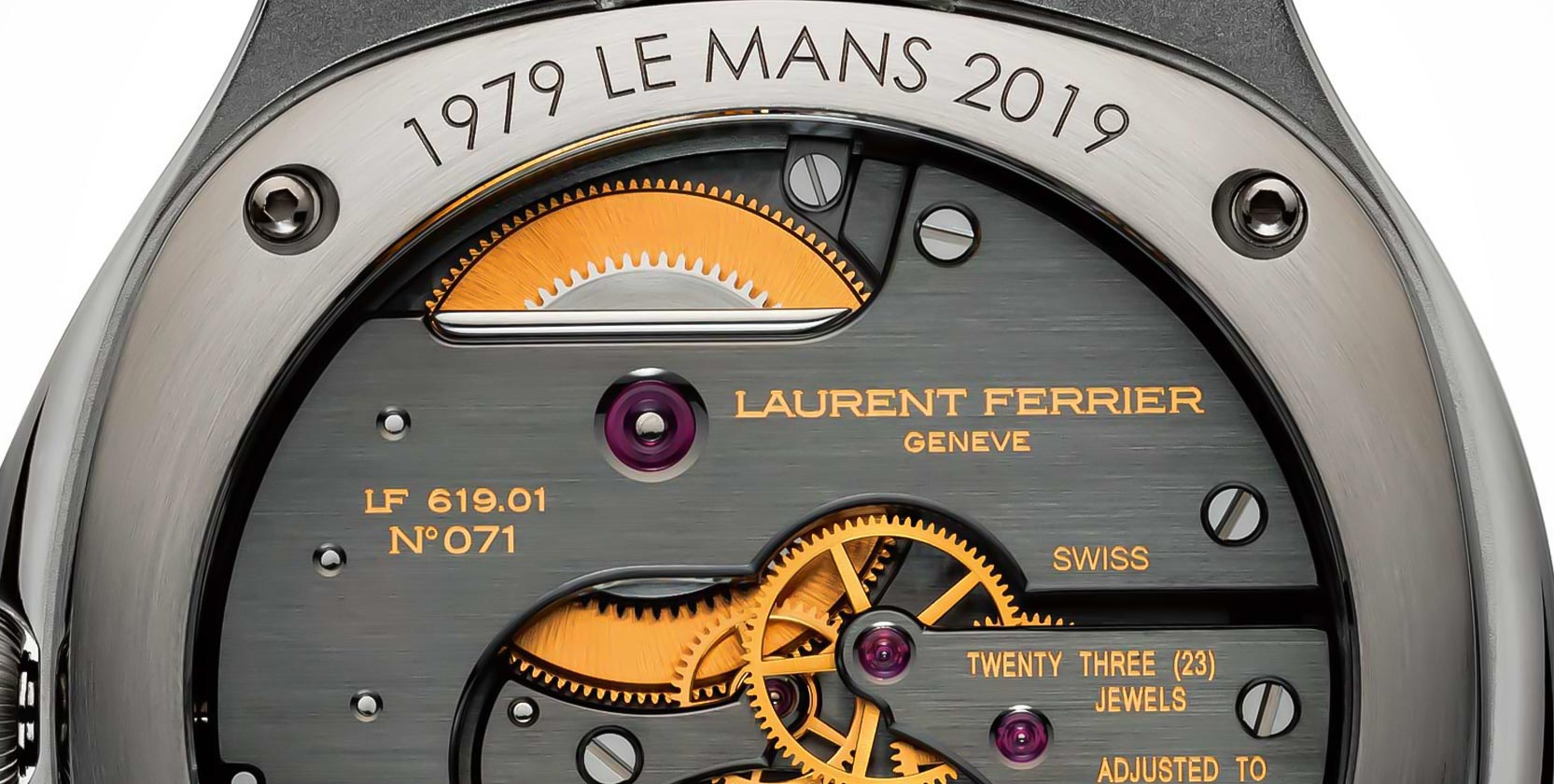

That same race Paul Newman and his co-driver placed second. It is incredible to think of Ferrier and Servanin celebrating in the same paddock as Newman and his team. Says Ferrier with a laugh, “People often describe us as being on the same podium as Paul Newman but Le Mans has no podium to speak of. However, we were of course well aware of him as he was our competitor. We were very impressed by his co-driver Rolf Stommelen. Despite all my racing, I had never really won any money and it was only in 1979 that I finally received a significant cash prize. So I took part of this money and offered a Patek Philippe Nautilus to François. On the back of it, I had engraved ‘Le Mans 1979’. Throughout my entire racing with François, we would always talk about what we might do together one day. That evening he proposed the idea of us starting our own watch brand. It intrigued me but I really loved my job at Patek so it would be something I put on hold for many years, until I finally felt I was ready.”

Indeed, it would take Ferrier a full 37 years at this famous watchmaking maison, where he would eventually rise to head the product development department, before he felt he was ready to create his own brand. To me, this is a remarkable contrast to the multitudes of young upstart watchmakers so eager to impart their vision of horology on the world. For Ferrier, he felt he had first of all to fulfil his obligation to his employer and second, wait until his vision for watchmaking was at the peak of its expressive possibility. He recalls, “I went to speak to my superiors. At first, they thought it was curious that I would want to leave just a few years from my retirement and the pension it would provide. I explained I was leaving to create my own small brand. I suppose it was not normal for someone my age to leave to start something new in their early 60s. But I finally knew it was time. Part of the motivation was the idea of being able to collaborate with my son Christian, who was at Roger Dubuis, working on movement development. I suppose it is the dream of every father to be able to create something together with his son. It is also a very complementary relationship because I like to focus on the design of the watch even though I also love the technical aspects of the movement, while he loves to focus on the technical aspects even though he has a huge appreciation for design. It was really the opportunity to create our dream watch, the exact type of watch we would love to wear ourselves. We knew we wanted to create a watch that was perennial that resonated with a great classic watchmaking language that we both loved. We also wanted the watch to express that dynamic contrast I speak about often. To have a wonderful discrete language on the dial side, and then to have a real vision of virtuoso watchmaking on the movement side.” The first manifestation of Laurent Ferrier’s vision for high watchmaking did all that and more.

Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral

I recall the first time I heard of Laurent Ferrier, it was from one of the watch collectors I respect most in the world. This is a man who is in possession of both a Patek calibre 89 and some of George Daniels’s most important works. So, when he professed his admiration for Laurent Ferrier, I was eager to learn more. But being in the presence of the Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral was an experience I was not prepared for. Immediately I was swept up by a powerful sense of Proustian nostalgia. It struck me deep in my emotional epicentre that it expressed precisely the style of watchmaking I longed for but had not even realized I missed. At 41mm in diameter, it was certainly modern but not oversized. But the delicacy with which the grand feu enamel dial, the lithe elongation of the Roman numerals in an act of interpretative brilliance that rivaled even Louis Cartier’s mastery of typography, was the first thing seduced me.

Everything, the position of the sub-seconds, the slate grey used for the minute track and the ivory cream grand feu enamel of the dial was perfectly executed. If the dial of a watch can be likened to the face of a person, it was simultaneously arresting in its beauty and somehow tremendously warm and inviting because of its familiarity. Ferrier laughs when he recalls telling Servanin that he wanted to create his first watch as a round three-handed watch with an ivory dial and Roman numeral indexes. In the context of the first decade of the new millennium, where watchmakers were experimenting with different modernist approaches to displaying time, this seemed almost wilfully anachronistic. Ferrier says, “François would later tell me that of all the ideas to start the brand he considered it the least inspired. This was of course before he saw the watch.” The Classic Tourbillon instantly awakens a longing for true classical watchmaking from the 19th century. Says Ferrier, “The idea is how do you design something that brings out this emotion yet it is totally original?” And originality is indeed prevalent in his design.

Ferrier’s Roman numerals are long and graceful and unlike any other I remember. His uniquely-shaped hands are similarly long and sleek. Ferrier names these hands ‘Assegai’ models, and they are inspired by the javelins used by the legendary Zulu warriors. The magic of the grand feu enamel dial really comes to light when Ferrier explains the delicate use of complementary colours. He explains, “If you look closely, you’ll see the minute track is a type of slate grey as opposed to the black of the indexes. The same thing with the signature and the words ‘Tourbillon Double Spiral’. These are rendered with a softness and delicacy that makes them look like they have faded over a century.”

When you touch a Laurent Ferrier case, it too exudes a sense of familiarity. Every surface has been modulated to feel like a caress on the skin. The term ‘Galet’, which Ferrier gave to his very first case design refers to a pebble. And this was precisely what Laurent Ferrier had in mind. He explains, “I wanted to create a case that had all the satisfying tactile smoothness of a pebble you find in a river whose surfaces has been worn smooth by time and water, so that no matter where you touch it you feel this sense of tranquillity and perennialism.”

Ferrier recalls multiple times during his career designing and prototyping cases where endowing a round case with a soft organic smoothness suddenly made it a pleasure to wear. At the same time, he wanted to energize his design with the inclusion of sharper, straighter lines, which he applied to the profile of his lugs. He explains, “As someone who loves cars, I always felt the best automotive design mixes soft, rounded feminine lines with stronger, more masculine ones. This creates an amazing dynamic tension, a sense of energy resulting from the contrast and I wanted to apply this to my Galet Classic model.” What is interesting is that even though the case for Ferrier’s first watch is 12.5mm in thickness, necessitated by having a tourbillon located at the back of the watch, it wears like a much thinner watch because of the way almost every line is expressed as a curve. Finally, the moment you turn a Laurent Ferrier watch over, is to be utterly obliterated by the beauty of the movement. In this case, the devastating richness of finish and the magnificent 19th-century Vallée de Joux pocket watch architecture of the tourbillon calibre.

But why start with a tourbillon? Says Ferrier, “There are certain complications such as a split-seconds chronograph that I love, but these are very delicate mechanisms and have to be treated carefully as they are fragile. What I like about the tourbillon is that it is, of course, difficult to poise and regulate. But once this is correctly done, it continues to run with great stability. For me, it was very important that our first watch be an incredibly reliable one and that all the owners would have a great experience with it.”

Importantly, Ferrier decided to make his Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral a masterwork of subtlety, not just with the restrained beauty of his dial, but by also placing his tourbillon at the back of the watch. He explains, “This was very important to me. I wanted my watch to be a symbol of discrete elegance, where the owner keeps the secret of its incredible complexity to himself. He has the opportunity to share this with his friends, but only when he chooses.” In a world dominated by social media and perhaps aggressive oversharing, Laurent Ferrier’s watches militated against bombastic extroversion with intentional and wonderfully charming understatement. In the context of 2008, with the world swept up by a financial crisis, this became something very significant, an expression of sensitivity and taste. Interestingly, in 2020, in a post-COVID-19 environment, this concept of discrete elegance is perhaps more relevant than ever. Says Ferrier, “Eventually I was asked to make a version of my watch where the tourbillon could be viewed from the front, but whenever possible, I prefer to design my watches to be the ultimate statements of restrained beauty.”

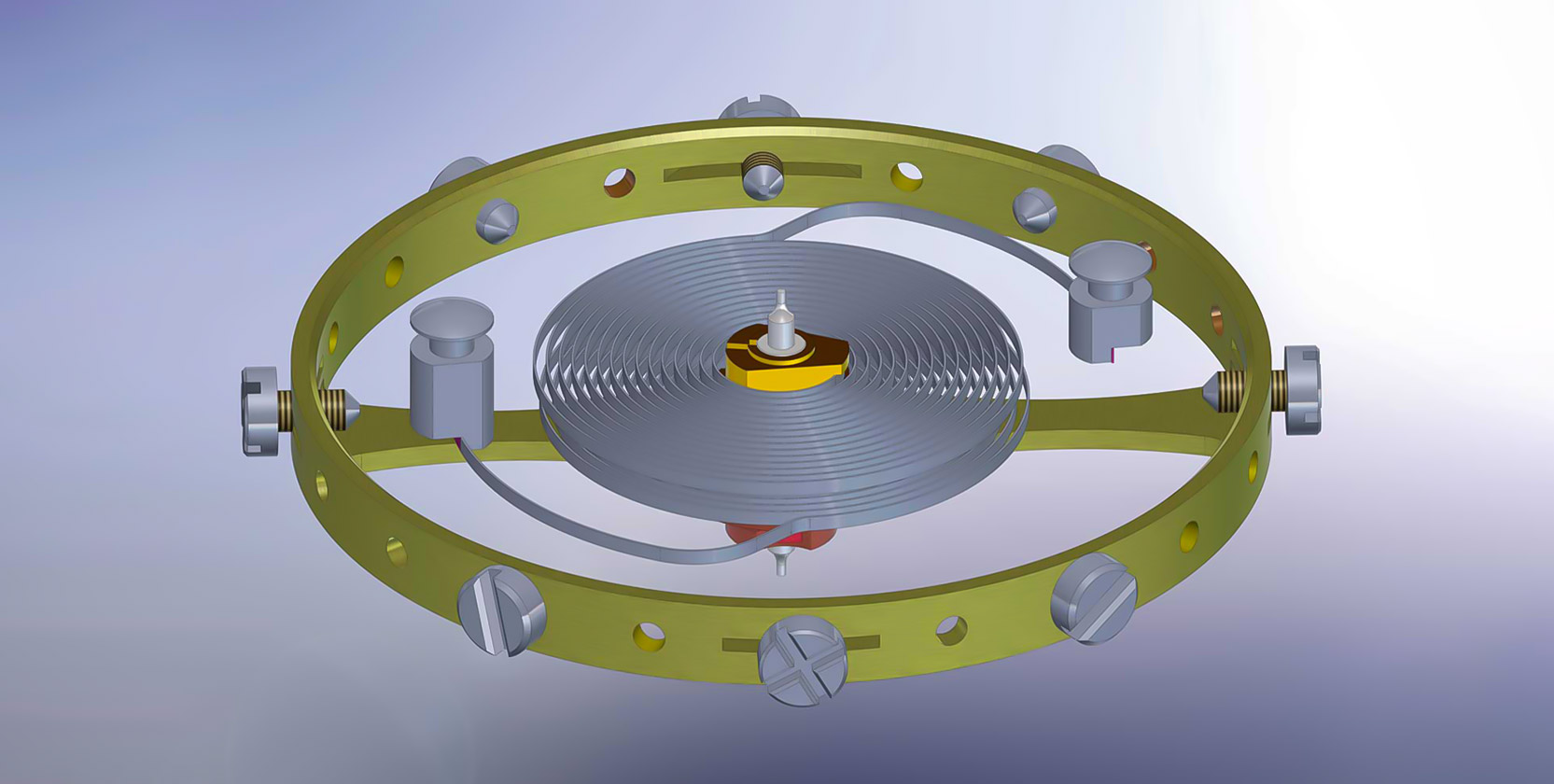

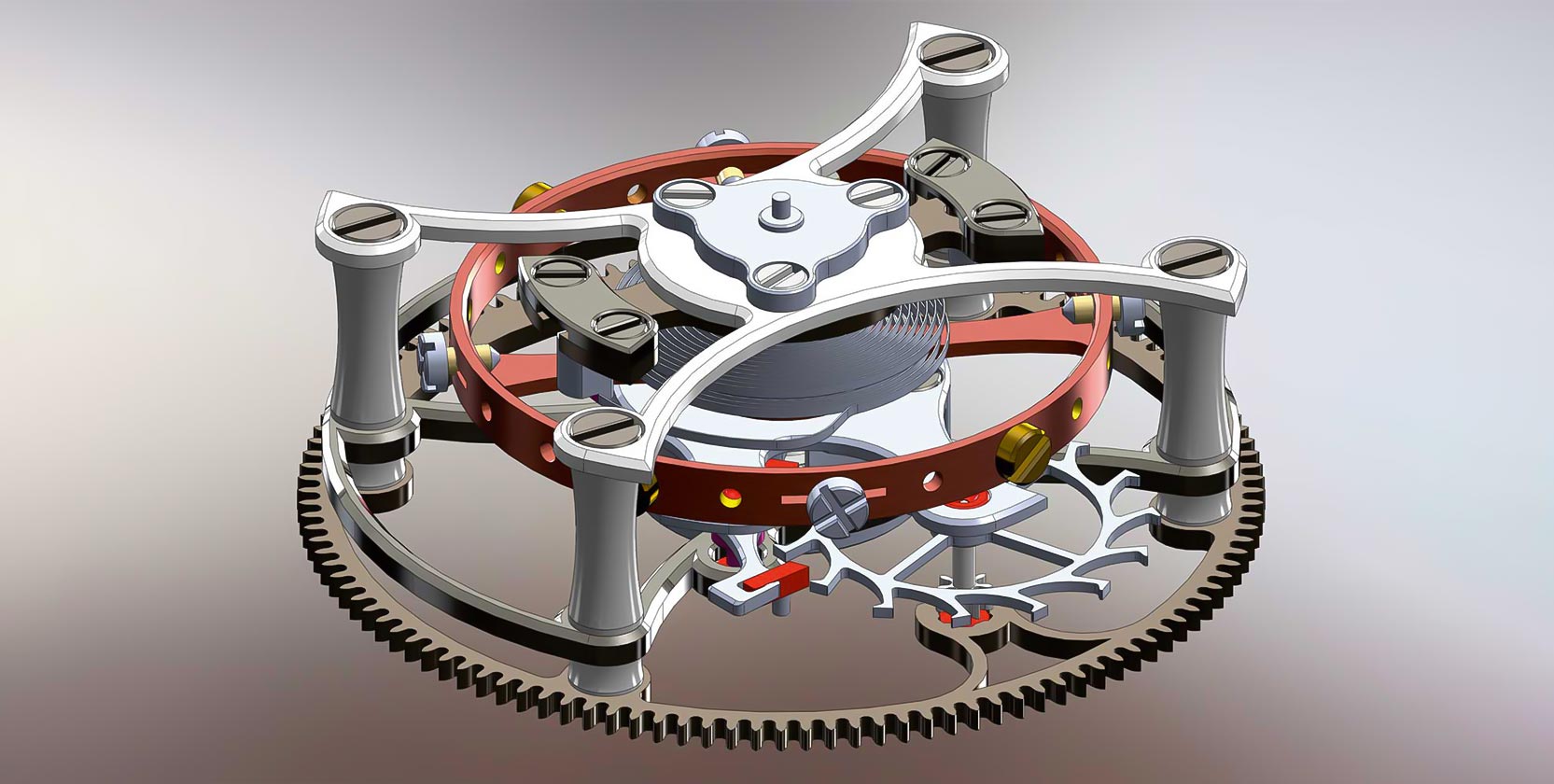

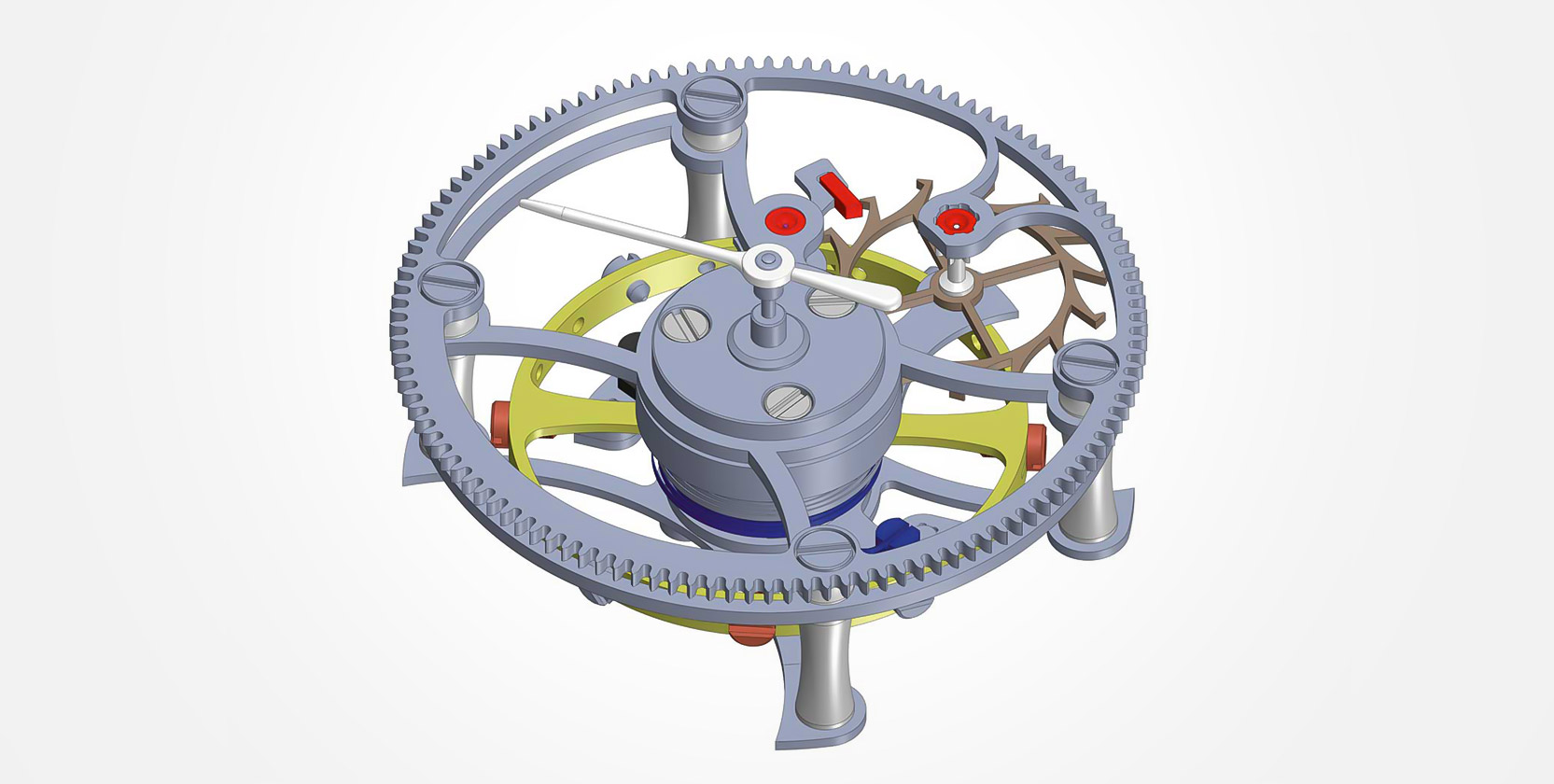

What is certainly not restrained in his first horological overture was the utter-transcendent magnificence of his 31.6mm-wide, 5.57mm-thick calibre LF 619.01. To create this movement, Laurent Ferrier and his son, Christian, reached out to old friends, and former colleagues from his time at the famous manufacture, who had since founded their own watchmaking workshop, La Fabrique du Temps. They had worked at Patek Philippe on complicated watches before moving to Franck Muller to collaborate with the legendary Pierre-Michel Golay of Gérald Genta on, amongst many things, a grande sonnerie. The movement that they would create with Laurent and Christian Ferrier would be one of their milestone achievements. Says Ferrier, “There have been many beautiful tourbillon movements, but my favourites were 19th-century pocket watches made with Vallée de Joux ébauches. So we decided to create a movement that expressed this style of watchmaking. At the same time, we wanted to bring an added technical dimension to the tourbillon. That’s when we came up with the idea of a double balance spring.”

Says Christian Ferrier, “The idea of the double spiral, or balance spring, has to do with optimising concentric breathing. A balance spring depending on its orientation will have a tendency to develop more in one direction than the other. As wristwatches adopt numerous positions throughout the day, this can also place unequal friction on some of the regulating elements such as the balance staff. The idea is that by placing two balance springs in opposing directions—head-to-tail as Ferrier calls it—the two springs offset each other and allow for regular and uniform development of both springs. This works particularly well in combating errors caused by gravity. As the original purpose of the tourbillon as designed by Abraham-Louis Breguet was to compensate for errors caused by gravity on the sensitive regulating organs of the watch, in particular the balance spring, we thought it would be particularly meaningful to elevate the performance of our tourbillon with the double balance spring solution.”

Says Laurent Ferrier, “For me every element of the watch should have a meaning and be rooted in historical significance. Yes, it is interesting to use a double balance spring in any movement because it helps to offset gravitational errors, but even more meaningful to use it in a tourbillon because you could imagine Breguet being pleased by this idea. The fact that together these two springs better hold the centre of the axis of the balance even as they turn within a one-minute cage seems to really strike a chord with collectors that love high watchmaking and its history.” In order to achieve this innovative solution, Ferrier tapped Precision Engineering AG to create the two balance springs. The company uses a proprietary material named after professor Reinhard Straumann who patented the material Nivarox.

What is extraordinary about the Laurent Ferrier Tourbillon movement calibre LF 619.01 is the beauty of its architecture. Bridges are executed as stunning and powerful horizontal expressions of masculine design. The gear train is clearly delineated, and your eye naturally follows the pathway from barrel to second wheel to third wheel. Where a lot of tourbillons are designed so that their third wheels engage with the pinion of the tourbillon cage, Laurent Ferrier opted for a different design. Here, the third wheel drives an intermediate wheel, which engages directly with the exterior of the tourbillon cage. A wonderful detail is that this tourbillon cage in turn drives a small seconds indicator on the dial side.

Says Laurent Ferrier, “I was surprised to discover that there are little tourbillons with a sub-seconds indicator at six o’clock. I suppose it has to do with the complexity of creating a functional seconds indicator on top of the tourbillon. I’ve always loved the beauty of a three-hand chronometer and when I had the opportunity to create my tourbillon, I wanted it to have precisely this appearance from the front of the dial.”

For watch lovers, discovering this movement is like being swept up in a love affair of extraordinary passion. The barrel features a decidedly old-school blade-style click ratchet, which has been mirror polished to such a high level that it doesn’t reflect light. All five of the bridges (excluding the tourbillon bridge) receive Geneva waves contrasted by stunning hand bevelling on their angles. While many brands shy away from sharp bevels as these have to be painstakingly created by hand, Laurent Ferrier almost goes out of his way to supply these in force. But it is his tourbillon bridge anchored by two fixed points on the left and by one point on the right that is his high finish tour de force, the orgiastic crescendo to the visual opera of his creative brilliance. The rounded left side of the bridge receives this same mirror polish or spéculaire, while the left side provides extraordinarily perfect sharp internal angles which are the single most challenging type of hand bevelling there is.

Says Ferrier, “For those that understand these details, I thought it would make them smile to see a movement intentionally designed so it could only be finished by very skilled hands. Of course we make about 150 watches a year so we are able to devote the time, energy and affection to every one of our timepieces.” Indeed, every countersink and screw head has been mirror polished to perfection and added together becomes a visual experience that is horological edification at its very finest. The Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral was launched in 2010 and soon developed a cult reverence that culminated in its winning of the 2010 Geneva Grand Prix.

Classic Secret Tourbillon Double Spiral

In 2011, Laurent Ferrier unveiled an intriguing version of the Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral. Laurent Ferrier featured a dial that could be retracted at 240 degrees to reveal a second dial underneath. That dial made as a bespoke order for each client could be gem-set, gold-engraved or miniature-painted. He explains, “The Secret was actually the first watch that I designed. I love the idea of a highly personalized dial. But because the philosophy of our brand is about discretion, we liked the idea of being able to keep an amazing artwork as something very private. I came up with the idea of a dial like a fan that would open to reveal a second dial underneath that was painted or decorated with a motif.”

The Secret can be opened on demand using the pusher co-axially mounted on the crown. But at the same time, you can program the dial to open from a specific time to another. If after dinner, from nine to midnight, if this is your time for personal reflection, then the dial can be programmed to open a full 240 degrees during this period. Over the life of this charming model, Ferrier has collaborated with extraordinary artisans like Anita Porchet, the late Dominique Baron and others. Each Secret is a bespoke creation limited only by your imagination.

The Classic Micro-Rotor

Launched in 2012, the Classic Micro-Rotor featured an automatic movement wound by a small fan-shaped mass mounted on a high-polished bridge. However, what was hidden within its depths was an escapement created by the legendary watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet. More than just an accessibly priced Laurent Ferrier, the Classic Micro-Rotor soon developed a passionate following. Says Ferrier, “Once people started to notice the Tourbillon Double Spiral, many of them began to approach me to ask, ‘We love your style of watchmaking but is it possible to create something that is more accessible in price?’ For Christian and me, this was important because we wanted people who loved our watches to be able to wear them. So, we began to have a conversation about a simpler automatic watch.” Says Christian Ferrier with a smile, “Well, of course my father would say simple, but in fact the movement we arrived at was anything but. I always liked that the tourbillon model and the Micro-Rotor model appear identical from the front of the watch. This was always my father’s philosophy that the complexity and technical value of your watch should be something you keep for yourself. However, we wanted owners of the automatic watch to also be able to turn their watch over and be able to feel a similar emotion that owners of our tourbillon feel.”

How did the father and son arrive at the unique combination of automatic winding and a novel escapement? Says Laurent Ferrier, “I love the practicality of an automatic movement. But so much of the experience of owning a Laurent Ferrier watch is the enjoyment of the movement, so we couldn’t cover this with a full-sized rotor. We decided, along with La Fabrique du temps, to mount this rotor on a bridge that resembled a tourbillon bridge that received the same level of mirror polish. Similarly, the bridge for the balance wheel is inspired by our tourbillon bridge—this is also mirror-polished and with sharp internal angles that can only be created by hand.”

But there would be one more element to Ferrier’s automatic calibre FBN 229.01 that would be obscured from the naked eye. Says Christian Ferrier, “When Breguet created the tourbillon he was trying to solve the issue of errors created by gravity on the hairspring and the escapement. But he was also trying to resolve the issue of oil. In fact, one of his most famous statements is, ‘Give me the perfect oil and I will give you the perfect watch.’ He understood that lubrication or more specifically the loss on parts had a very negative effect on watches. Because of this, in 1789, he created the natural escapement.” One of Breguet’s signature inventions, the natural escapement uses two escape wheels turning in opposite directions to all but reduce the sliding friction found in most escapements. In Breguet’s design, the first escape wheel is driven by the mainspring, while the second escape wheel is driven by the first escape wheel. This way the release of the escape wheels, which alternates, is in each direction to reduce sliding friction. A lever in the centre rocks back and forth and is what provides the impulse to the balance wheel.

The challenge facing Laurent Ferrier was to define a functional balance between the limited thickness of an automatic movement and a high degree of efficiency for winding the barrel. Achieving this implied finding a system ensuring perfect winding in order to compensate for the lower inertia of a small oscillating weight. In fact a micro-rotor needs as twice as many rotations (300 vs 150) needed for one complete turn of the ratchet wheel. Thanks to the efficiency of Laurent Ferrier escapement, the number of rotations needed can be reduced by one third—to approximately 200 rotations—a gain for the owner of the watch.

This exclusive double direct-impulse escapement in silicon, directly on the balance, has been inspired by the father of modern horology, Abraham-Louis Breguet. This modern construction, associated with the use of cutting-edge materials, maximises the restitution of energy. Thanks to the excellent efficiency of this escapement, the moment of couple (= torque) required to wind the mainspring is reduced and hence optimizes the movement winding. Inspired by the concept of the detent escapement this escapement has the advantage to give two impulses per oscillation (1 oscillation = 2 vibrations). This means that Laurent Ferrier’s movement frequency of 3Hz (21,600vph) allows to impulse the balance 21,600 times per hour.

To use a metaphor, we can explain the double direct impulse by comparing with a swing: with a detent escapement you push the swing once and you wait until it bounces back to give it the next impulse; with the double direct impulse escapement you push the swing and another person opposite pushes it back on his side.

Says Christian Ferrier, “Breguet’s idea was brilliant. He implemented the escapement in 20 pocket watches. But the escapement was extremely difficult to manufacture with the tools of this era as the tolerances had to be perfect for the wheels to have no play but be able to move freely. As we discussed the natural escapement in collaboration with La Fabrique du Temps, they came up with the idea of using advanced technology and materials, specifically nickel phosphorus, for the escape wheels. These are galvanically grown and have tolerances that are incredibly precise, down to the micron. For the lever they suggested we use silicon and because of these materials, we were able to reduce to a minimum the use of lubrication.”

Says Laurent Ferrier, “I think it is wonderful that we were able to implement the famous natural escapement, I must say we were very impressed with the results of this escapement. Like the tourbillon, it is challenging to install and regulate but once this is correctly done, it has proven to be incredibly stable. It was also important to me that we expressed the same movement design language in the micro-rotor and so you see that on the angle of the upper bridge we created a sharp internal angle just to show collectors who appreciate these details that this movement is hand finished to the same standard as our tourbillon.”

The dial design of the Classic Micro-Rotor exudes a wonderful minimalism invoked here by long pointed baton markers that perfectly complement the finesse of Ferrier’s signature Assegai hands. The minute track, rather than being printed or applied, uses a pierced technique that results in the relief effect of 60 tiny bowl-shaped indexes. Says Ferrier, “This was a technique that was once popular but has largely disappeared. It is an example to me of a technique that is beautiful yet very subtle and as such, perfect for our dial.” Upon launch, the Classic Micro-Rotor became one of the most coveted timepieces around and struck a chord with the world’s leading watch experts. So much so that Aurel Bacs, senior consultant at Phillips Watches and the world’s leading watch auctioneer; Auro Montanari, the legendary Italian collector; Ben Clymer, the brilliant founder of Hodinkee; and Eric Ku, the owner of vintage Rolex forums, and a vintage watch guru and Rolex expert, all ended up creating unique executions of this watch for themselves.

Square Micro-Rotor

Launched in 2015, the Square brought an all-new energy to Ferrier’s lineup. This cushion-shaped 41mm by 41mm watch added an injection of sporty energy. Says Ferrier, “I was always attracted to this style of case. While the cushion shape is very distinct from our Classic, it precisely follows our ethos concerning a form that provides a great tactile pleasure to wear.” The Square was the first Laurent Ferrier watch to be produced in series, in steel, and won the prize for Best Horological Revelation in 2015.

Over the course of his life, Laurent Ferrier has made several special versions of the Square that demonstrate his extraordinary design acumen. Indeed, the watch has become something of a showcase for Ferrier’s imagination. One of these models is the Boréal launched in 2016, which features a stunning luminous sector dial. There are two more sector-dial versions with applied indexes and track made for US retailer Swiss FineTiming (silver dial with applied Arabic numerals in 2016 and salmon dial with applied Breguet numerals in 2017) and, of course, the wonderful original sector-dial watch created for the Only Watch charity auction in 2015.

Beating inside the Square is the FBN229.01 micro-rotor and natural escapement movement that was introduced in the highly successful Classic Micro-Rotor. The Square also comes in a Regulator configuration where each hand is placed in a different position on the dial, emulating a watchmaker’s regulating clock.

Classic Traveller

One of Laurent Ferrier’s objectives in the expansion of his complication vocabulary was to retain the beautiful design purity of his brand while adding real and pragmatic functions. In 2013, he did just that with his Classic Traveller. Says Ferrier, “One of the realities of the modern world is constant travel. So I wanted to create a watch that addressed the need to read both home time, local time and date at one glance. The first thing that struck me is that many watches have the date synchronized to home time which is technically incorrect. Because wherever in the world you are, the local date is the information relevant to you. The second thing I noticed was that even when the date was synchronized to local time, it would be brought forward but most often it could not be brought backwards.” Thus motivated, Ferrier embarked on a mission to create one of the easiest to use, functionally innovative and of course classically stunning watches on the market.

He named this watch the Classic Traveller. This watch would be powered by his micro-rotor, natural escapement movement. But what would make a huge difference to discerning watch collectors is that the calibre LF 230.02 is an integrated movement. That means that the additional mechanism to display the home and local time is integrated into the baseplate of the movement. Most other brands would have simply added a module to the base caliber. But as Christian Ferrier explains, this would not be the prevailing philosophy at Laurent Ferrier.

The design of the watch is a perfect expression of Ferrier’s focus on intuitive displays of information. He explains, “When someone looks at a watch, their eyes will naturally move to certain displays. I want to create a sense of visual logic so that when someone looks at it, you don’t even have to explain how to operate the watch. You understand intuitively. For example, on the Traveller, your eyes will move from left to right as this is the direction in which we read. On the left of the case at 10 and eight o’clock, you will find the two pushers to move the local time hour hand either forwards or backwards. The lower advances the hand while the top pusher makes it go backwards.” At nine o’clock on the dial, you have a display for home time. This is told with a dragging indication and the aperture is made larger than that of the date for two reasons. First, that you immediately identify its function; and second, so you can see the hour just before and just after your home time. At three o’clock, you have the date. This indication follows the local time both forwards and, very importantly, backwards. Then you have a small seconds indicator at six o’clock which is a visual signature for Ferrier’s brand.

The dial iconography of the Traveller is an exciting departure from the ultra-classic nostalgia of both the Tourbillon Double Spiral as well as the Micro-Rotor watches. Here we find a much more contemporary energy expressed through the use of long, pointed applied hour markers called drop-shaped and printed minute markers in high-contrast relief to the matte or contrasting finished dials. The watch measures 41mm in diameter and is 12.64mm thick. From the back, one visual clue that this is a different timepiece from the Micro-Rotor is the use of a lovely barleycorn guilloche pattern on the rotor. The standard Micro-Rotor watch has a fan-shaped engraving applied to it.

École Micro-Rotor

The year 2017 was a momentous one as it marked the launch of Ferrier’s new case shape, this time one that paid homage to his roots. The École’s design was based on the pocket watch that Ferrier crafted to graduate from watchmaking school. Says Ferrier, “As I began to think of a second round case shape, I first asked the question what its purpose would be. The Classic has a very specific form that is very curvaceous. However, when it came to enlarging its dimensions to add more of the complications, I didn’t like the effect on its proportions. As such, I began to think of a case that would be particularly well suited to be the home of complications such as the annual calendar and the minute repeater that we were developing. Interestingly, I found myself back at the very origins of my journey with watchmaking. As I mentioned, to graduate from watchmaking school in 1968, I made my own pocket watch. This timepiece was very much inspired by the watch design I loved from the 1950s. Interestingly, I think I can now see much of the design philosophy that would take shape later in life in evidence in this project. In particular, I liked the case of this pocket watch and thought it would be a strong inspiration for a new model. I called this École in reference to its link to my school project.”

Of the various case designs that emerged from the ’50s, one of the most beautiful was the ‘Disco Volante’ case shape used by several high watchmaking maisons for some of the most iconic watches from this period. This is a serene round ‘Flying Saucer’ shape that was counterpointed by soldered lugs. However, Ferrier’s approach to this style of case was markedly different. His École takes the iconography of the Disco Volante and softens it with a sensitive organic plasticity to imbue that same feeling of having been worn smooth by water that is in evidence in his Classic. The result is a watch that is an even higher expression of harmony and tranquillity.

While the Classic is about the contrast between curved lines and straighter ones to result in a dynamic tension, the École case does not have a single straight line. Its bezel and case band are curved, and even the caseback is rounded. Every section of this three-part bassiné case feels sculpted by nature. So, the dynamic contrast here is achieved through the muscularity and power of the lugs with their curved shape but straight sides. Each lug is capped with a cabochon that covers the spring bar and endows the design with a kind of Officer’s case aesthetic, which is augmented by the ball-shaped crown that is a pleasure to wind. The final result is a case that is more curvilinear than a traditional Officer’s case, but more functional and robust than a Disco Volante.

Some collectors have posited that the form of the École is reminiscent of these early wristwatches that had lugs soldered onto them for use by pilots and military officers. But I feel that the ethos of the École is far more nuanced and charmingly executed in its wonderfully rounded form to be so easily described with this simplistic comparison. Launched in 2017 with a diameter of 40mm, the École immediately became a worthy sibling to Ferrier’s other case shapes.

With his École, Ferrier’s dial design would reach an apogee of purity. Drop-shaped hour markers at 12, three and nine o’clock were contrasted by a printed minute track. The sub-seconds scale would only feature four hash marks adding to the Zen minimalism of this act of horological haiku. Regarding the surface decoration of the dial, which features contrasting sections of vertical brushing for the main dial and circular brushing for the section beneath the indexes, Ferrier was again inspired by the great Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Says Ferrier, “Before Breguet watches were very ornate in design, he was the first person to create a restrained and subtle design for the dial. In so doing he became the world’s first modern watch designer. His idea was to use different styles of guilloche to help in the identification of each section of the dial. So the small seconds sub-dial would have a different decoration from the power reserve indicator, for example.” While looking at a ‘guilloche fait main’ Breguet watch today in comparison to a Laurent Ferrier, the styles of watchmaking could not be less similar. However, the use of subtle dial decorations to create beauty while enhancing visibility is a strong philosophical allegiance between the two watchmakers. Of note is that Ferrier created a steel version of this watch, and chose a rougher decoration for its micro rotor movement, recalling the original materials uses in prototyping, such as brass, which offers a contrast with steel. Further hand-finishing skills applied to the movement include shot-blasting, known as microbillé, and mirror polishing for the parts in steel, including the balance cock. This gives a similar aesthetic as the frosted finishes that were often used by British watchmakers in the 19th century. The gold versions of this watch received the classic Geneva stripes decoration.

The dial of the École is also configured as a regulator. This is based on large watchmakers’ clocks that were used to regulate movements. For maximum visibility from all parts of the atelier, regulators had each of their hands placed at different positions on the dial. In the case of the École, hours are placed in a sub-dial at 12 o’clock, seconds at a sub-dial at six o’clock and the minutes are read off the large hand in the centre of the dial.

The École Annual Calendar

Shortly after the launch of the École, in 2018, Ferrier introduced his first complicated version of this timepiece. The annual calendar complication, which is one of the most pragmatic in the realm of high watchmaking, was introduced in 1996 by Patek Philippe. This watch marries the intelligence of the perpetual calendar, which automatically compensates for the shifting 30/31-day rhythm of the months, with the more accessibly priced and functional robustness of a simple calendar, which necessitates the manual correction for any month with less than 31 days, altogether five days during the year. In an annual calendar, you only need to make one adjustment each year by manually adjusting it on the last day of each February.

What was important for Ferrier was that his annual calendar introduced an ease of adjustment that was not present in other watches. He explains, “I’ve always loved the annual calendar. Here is a watch that provides a correct reading for date, day and month at all times with only one adjustment required each year. But the reality is that as with all calendar watches, owners have a tendency to rotate with other watches, and eventually, the calendar information has to be reset. With other annual calendars, a system of pushers integrated into the side of the case are used and each display is operated using the corresponding pusher. This means you have to create an unnecessarily complex case, and also, if you don’t have an instrument to adjust these pushers, you are unable to set your calendar. At the same time, there has been a solution where the annual calendar information is synchronised but then if you accidentally set the information too far in advance, you can’t turn the date backwards. For our annual calendar, we wanted to have all the practical benefits of crown operation but a date that could be turned both backwards and forwards.”

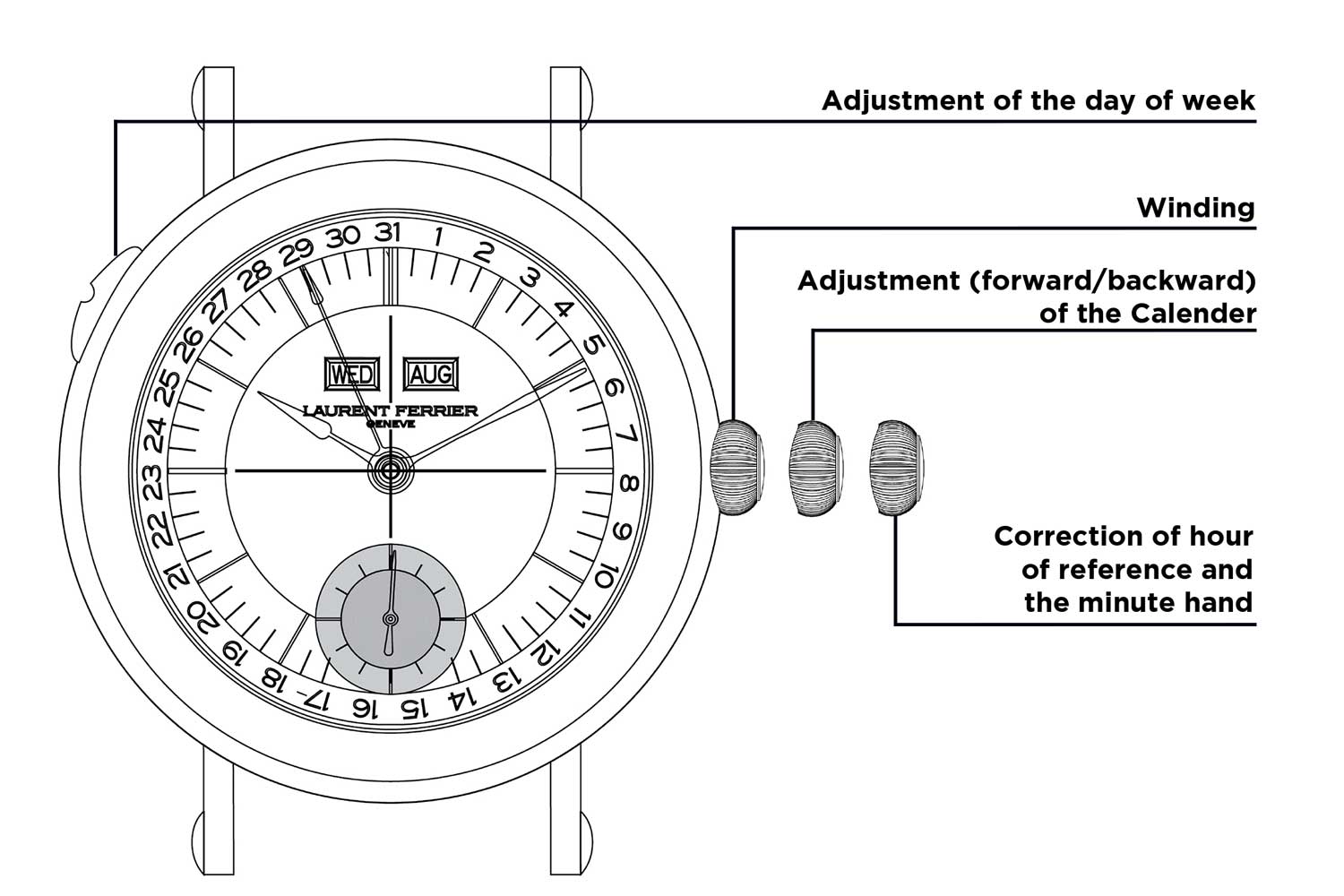

This is how the Annual Calendar is set. Position one on the crown is for charging the barrel of the watch’s manual-wind movement. Pull the crown out to position two and you can now rapidly advance the date in either direction. However, by turning the crown backwards and forwards in one motion, you can advance the month. Days of the week are adjusted using the pusher integrated at 10 o’clock into the case. So in terms of sequence, you would first adjust the months, the date, then pull the crown out to third position. After that you can easily use the pusher to set the correct day of the week.

The dial of the Annual Calendar is a masterpiece of Ferrier’s intuitive approach to information display. Day and month are read in twin bevelled horizontal apertures that are located at 12 o’clock just above the Laurent Ferrier signature. The month is read off a centrally mounted hand and a scale that is printed on the perimeter of the dial. This is reminiscent of one of Audemars Piguet’s first perpetual calendar wristwatches, the reference 5518 from 1955. Indeed, for me, even the wonderful font selected by Ferrier with the open ‘6’ and ‘9’ and vertical serif ‘7’ pays tribute to the masterpiece while providing a thrilling contemporary twist by being rendered in bold colours such as Royal Blue. But it is in the demarcation of subtly different levels and decorations on the dial that you see Ferrier’s true genius. The centre of the dial sits slightly higher and uses a vertical satin brushing, the minutes receive a circular-brushed finish and slope gently away from the centre of the watch, while the date track sits on an opaline finish on a slightly recessed plane. Similarly, the small seconds sub-dial is recessed and there is circular guilloche in the centre with an opaline track. And for the first time, Ferrier uses a crosshair motif on his dial which brings an added sporty dimension to the design. Additionally, the watch won the best ‘men’s complication’ prize at the GPHG in 2018.

Note that the Annual Calendar does not feature the natural escapement found in the Micro-Rotor. Instead, Ferrier has opted for a classic Swiss Anchor in its place.

École Minute Repeater

In 2019, Laurent Ferrier completed the complication range for his watches with a minute repeater created in collaboration with La Fabrique du Temps. Says Ferrier, “The roots of the minute repeater are one of the most charming in horology. Noblemen in the 18th century wanted to be able to check the time without having to resort to lighting a candle. So they would own a pocket watch that would play the time. By depressing a slide in the watch, it would ring out the time.” The format in which time is played on two gongs, one with a lower note and one with a higher note, is as follows. Hours are struck on the low gong, quarters with a combination of the two, and minutes on the high gong. Ferrier’s minute repeater finds the perfect home in the tripartite bassiné case of his École. As always, this timepiece is a masterwork of subtlety. The Laurent Ferrier signature is muted, and the minutes are described using small printed dots. Indeed, the words ‘minute repeater’ are so softly inscribed on the dial that your eyes have to seek out the words.

The steel case of the watch aids in the brightness and clarity of the minute repeater, which is activated using the large slide located in the traditional position at the left side of the watch. The movement, which is designed by Ferrier’s friends at La Fabrique du Temps and Christian Ferrier, is excellent in tonal quality. It should be noted that both these men have an incredible history with repeaters and have created an exemplary movement here that is typical of a Laurent Ferrier watch, restrained but technical at the same time. What is charming to see is the typical blade-shaped ratchet spring for the barrel, which comes from Ferrier’s very first movement, his Tourbillon Double Spiral, but now located on the same plane as the hammers and flying regulator of the repeater mechanism.

Bridge Manual

In 2017, Laurent Ferrier combined with independent watchmaking rebels URWERK on a unique watch for Only Watch. The resulting timepiece became one of the most hotly contested lots. But the shape of the watch left something to be desired for Ferrier. He explains, “The case was a bit bigger than what we were used too. But it started me thinking about a bridge-shaped watch that featured a wonderful curving case profile and that is how we arrived at the Bridge One.”

Launched in 2019, the result is a masterful work of old-world refinement. Of course, for Laurent Ferrier, the idea of placing a round movement inside a rectangular case did not sit well. Accordingly, he conceptualised an all-new rectangular manual-winding calibre the LF 107.01 specific to this model. Though the watch measures 44mm by 30mm and is 14.58mm thick, it is remarkably comfortable to wear because of the curve of the case. The Bridge is made in an enamel time-only version, a version with small seconds and a version with a sector dial.

Grand Sport Tourbillon

Launched in 2019, the Grand Sport Tourbillon was created to honor three major achievements. The first was to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the 1979 Le Mans third-place victory by Ferrier and his partner, François Servanin. This remarkable moment also set into motion the birth of the Laurent Ferrier brand. Secondly, the Grand Sport celebrates the 10-year anniversary of the 2009 creation of the brand, as well as the conceptualization of the Tourbillon Double Spiral. What is interesting to recall is that in honor of their third-place podium finish at Le Mans, Ferrier gifted Servanin with a Nautilus watch as a symbol of their friendship. Says Ferrier, “As we approached the 40-year anniversary of this race, I wanted to give him another watch to celebrate four decades of friendship and one decade of partnership. But this time, I wanted it to be a watch that I designed and that was powered by the engine that was most significant to both of us, the Tourbillon Double Spiral.”

For Ferrier, the Grand Sport Tourbillon would be the first watch he created that entered unabashedly into the world of sports timepieces. Says Ferrier, “I began to think back to those days that I was racing. And I started to think of a watch that I could wear in the cockpit, behind the wheel, that could live up to all the pressures of the 24 Hours of Le Mans.” Ferrier recognized first that it had to be perfectly ergonomic. He explains, “I went back to the Square which was my most sporty timepiece at the time. And I began to conceptualise a chassis around it. More of a tonneau shape which I always find comfortable to wear. I wanted the case to be rigid like a car and so I came up with the idea of it being held together by stems or rods that would be attached to the bezel and travel through to the caseback, where they were securely fastened. I wanted to use these hexagon socket headed screws because this is something we used often in racing.” Looking at the caseback of the Grand Sport, you can see Ferrier’s meticulous attention to smoothing every available surface, particularly in the integration with the watch’s rubber bracelet. Says Ferrier, “I thought immediately of a rubber bracelet because this is something you could wear under a racing suit and it would perform well and not get wet with perspiration.”

Ferrier also knew that he had to have the ultimate performance engine, specifically his amazing Tourbillon Double Spiral. Says Ferrier, “As I mentioned, I chose the tourbillon because it is actually a robust complication. But because our tourbillon is using the two hairsprings arrayed head to tail to maximise concentric breathing, this tourbillon performs incredibly well.”

Finally, Ferrier knew he had to have a dial that provided maximum visibility even under the duress of endurance racing. For this reason, he selected bright orange luminous indexes and hands. The case of the Grand Sport is 44mm in diameter, making it the largest timepiece in the Ferrier arsenal. Yet because of the intelligent strap integration, the watch wears easily even on smaller wrists. The Grand Sport is also water-resistant to 100 meters, making it the ultimate stealth sports watch perfect in the water or behind the wheel of your race car.

The LF 619.01 calibre, fully admirable on the back, bears numerous Laurent Ferrier signatures, and is absolutely stunning and elegant. It’s also treated with a dark ruthenium coating for a more muscular look. For 2020, the Grand Sport Tourbillon gains an integrated steel bracelet, with a three-link tapered design that reminds one of the engine blocks in a car. The matte finishing of the entire watch gives it a classic, weathered appeal. The dial, instead of the brown from last year, takes on a gradated blue to black presence, while the hour markers and hands remain the same.

Classic Origin Green

Laurent Ferrier watches are at their best when they are at their most subtle. Seemingly subtle, at least. Because as much as you may be looking at a time-only watch with a small running seconds, turn the watch over and you’ll be left with no doubt that Laurent Ferrier means business. But with a great sense of delicacy and elegance that only a few are able to appreciate. With this in mind, enter the Classic Origin Green, created to mark Laurent Ferrier’s 10th anniversary as an independent watchmaker, and only be available directly through Laurent Ferrier.

The watch is a time-only instance with a small running seconds placed in the traditional 6 o’clock position. The case is from the watchmaker’s Classic collection and features a round polished case. We would, however, be grossly mistaken if were to write the watch off there. Because that case is rendered in titanium. Grade-5 titanium specifically, as it allows for the high gloss polish we see here. Looking through the sapphire crystal glass, we see the beautiful gradient opaline dial that transitions from translucent green at its centre to deep green near its periphery; with 18-karat white gold drop-shaped hour indexes used for the cardinal points, and 18k white gold Assegai-shaped hands. Just above the hour indexes we’re presented with a railway track minute scale that doubles up with a 24-hour scale printed in a sharp tint of yellow, giving the timepiece a sense of sportiness. The same yellow colour is used to mark the scale of the small seconds that’s held within a stepped down sub dial.

Now, we turn the watch over to reveal the manual wound calibre LF 116.01, which is making its debut in the Classic Origin. As much as the watch has very classic elegant aesthetic outlook from the front, Laurent Ferrier has taken a left turn having used grade-5 titanium for it, no doubt a very contemporary choice. The movement’s bridges are finished in micro blasted, black rhodium, yet another contemporary direction, but the decorations thereafter are very much classical with hand polished angles on the bridges, mirror-polished screw heads and so on. It’s also important to note that the LF 116.01 has a free-sprung balance with the Breguet overcoil and Laurent Ferrier’s long-blade ratchet system. What is the long-blade ratchet system? It’s not seen much in modern watches but was widely used in pocket watches in a time long past. Essentially the bar has a spring retention on one end and a pawl finger on the other. When you are winding the watch, the ratchet wheel can, therefore, only be wound in one direction as allowed by the pawl finger.

Is Laurent Ferrier For You?

In conclusion, asking yourself if you are a potential Laurent Ferrier owner has a lot to do with understanding your fundamental philosophy in life. Laurent Ferrier watches are the ultimate in discretion and understated charm. These watches are for the individual that has style and elegance and a love for technical watchmaking, such as the world’s first tourbillon with double hairspring and details like grand feu enamel dials, but prefers to keep the value of his watch to him or herself. You might see his watch and like it, and you might not be sure if it is a modern watch or even a vintage watch, but other Laurent Ferrier owners will recognise it and know what it is.

Says Ferrier, “I like that Laurent Ferrier collectors form a sort of club, or close-knit community that is simultaneously very discerning but behaves with ultimate discretion. Perhaps in the post-COVID-19 environment where it can be perceived as not correct to display one’s wealth aggressively, we will see a return to understated, or I believe the Americans call it ‘stealth’ elegance. I certainly think that this will be one major shift in consumers’ mentalities, and I feel that Laurent Ferrier is the perfect brand to express that ethos.”

This story was originally published on Revolution. Revolution is one of the leading watch media titles, placing mechanical timepieces front and centre in a luxury-lifestyle format. Revolution is a global brand reaching a global audience, but with a strong knowledge of local markets and great relationships with top collectors and watch groups worldwide.