FeatureLeaders In Luminosity—What Makes The Glowing Parts Shine

We’ve come a long way from using radioactive radium and tritium in our watches to the much safer Super-LumiNova. Development in the area of luminosity comes from pioneering manufacturers and suppliers who like to build on their glowing reputations with patents and proprietary shining substances. Here’s a look at what makes your watches glow and who made them glow to begin with

May We Recommend

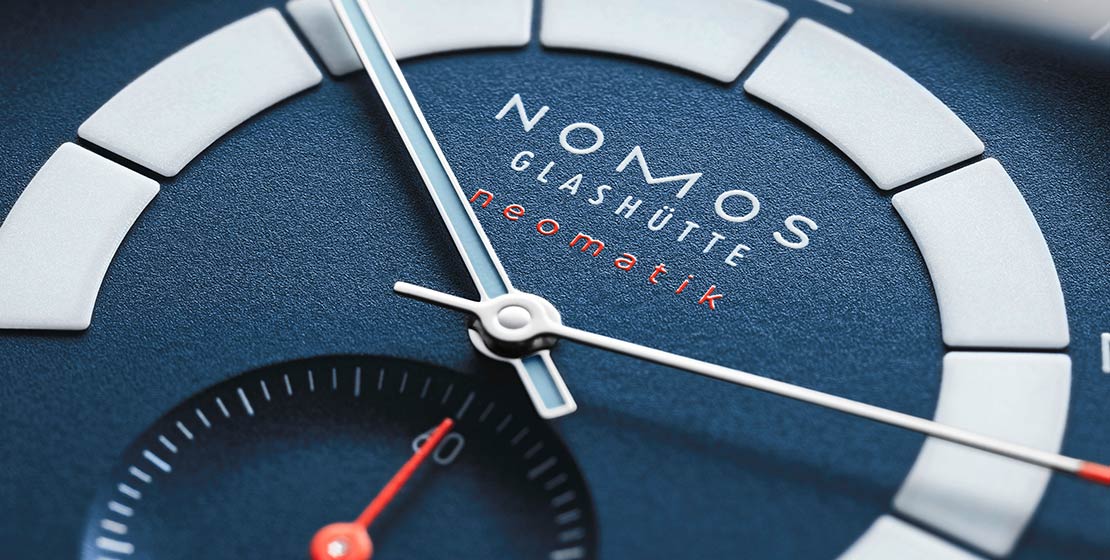

In all these years of wearing watches and seeing novelties at the watch fairs and manufactories, one aspect of the timepieces that always fascinates me—like I’m seeing it for the first time, every time—is the glow of the display. You can instantly tell which parts of a watch will glow in the dark, owing to the apparent coating of Super-LumiNova or some other luminous material—or ‘lume’—generally on the indexes and hands. If there’s a special part of the display or an indication that features lume without it being apparent, it always comes as a wonderful little surprise when they shine their little UV light on it to showcase the glowing parts. From releases in recent years, the Girard-Perregaux Bridges Cosmos and the Nomos Autobahn come to mind. The former features a globe and a sky chart with constellations, which unexpectedly light up when held under a UV light, or in the dark, even though the lume in the hands is pretty obvious. In the Autobahn, the speedometer motif on the dial is what shines bright, immediately elevating the automobile dashboard inspiration of the design with the luminosity.

Today, it’s possible to have a smattering of glowing parts in a watch, aside from the main markers and hands, but until a few decades ago, luminosity was a feature used quite judiciously. Or perhaps it was used too much, considering the harmful nature of the substances used for luminescence back in the day. But what causes any substance in a watch to glow at all? For those who might not know or recall the physics of it, let’s just briefly go back to the basics.

Behind The Glow

When your watch hands glow in the dark, what you’re seeing is phosphorescence, which is a kind of photoluminescence. The latter is the ability of a material to emit light after being exposed to an external source of light, due to the absorption of photons from the external source. A photon is the quantum of an electromagnetic field, such as electromagnetic radiation from light and radio waves. Ultimately, it comes down to the atoms of the glowing substance, whose electrons absorb photons, and get excited to a higher energy state, and then emit photons when the material ‘relaxes’, which we can see as light. Thus, phosphorescent materials absorb photons from external light, and then re-emit these photons as light that we see. This re-emission—and glow—occurs over an elongated period of time, over a period of many hours, in the case of phosphorescent paints used for watch dials. For phosphorescence to take place, what’s required is a phosphor, and an ‘activator’ to enhance the absorption and release of photons. The phosphor commonly used in glow-in-the-dark substances used to be zinc sulphide, which is relatively safe by itself, but is highly problematic when used with radium or other radioactive substances as an activator or an ‘excitant’.

Radioactive!

Radium alone can create luminescence without an external light source, because of the energy from radiation emitted by radium particles in it. With its emission of alpha particles and gamma rays, along with the beta particle emission of its decay by-products; radium is highly unstable and is also a radiological hazard. Additionally, radium decays to radon gas—a powerful carcinogen that causes death by cancer. Furthermore, radium’s radiation breaks down zinc sulphide—used as a phosphor in radium paints—quite like UV rays from the sun chemically break down plastic and other synthetic substances. Eventually, over years or even decades, radium paint will lose its glow, partly due to the deterioration of the phosphor. However, a dial with radium paint will continue to be radioactive, as radium literally takes millennia to completely decay, as it eventually ends up as a stable isotope of lead. The half-life for radium—1,602 years—is half the time it will take for it to completely decay. This means that any radium dial found today is radioactive and will certainly set off a Geiger counter, because no watch is over 2,000 years old.

Radiomir—The Radium’s Gone; The Name Has Stuck

Known for their origins as suppliers of instruments to the Royal Italian Navy, the Florentine brand Panerai were pioneers in the enhancement of the capabilities of diver’s watches. A major challenge in dive watches back in the day was their readability in the darkness underwater. In 1916, as part of their research and development for diver’s instruments for the navy, Panerai created Radiomir, which was a radium-based powder that lent enhanced luminosity to their watch dials. Radiomir paint created thereof was among the brightest-glowing lumes at the time. The patented substance subsequently led to an entire collection being named after it. Eventually when all radium-based luminescent substances were found to be highly radioactive and very likely to cause lifelong diseases and ailments on exposure, even Radiomir stopped using radium. When Panerai watches became available to the public, the signature Radiomir design template continued, as it does to this day, but with no radium on it.

Alternatives To Radium

Clearly, radium was a bad idea for many reasons. Women in watch factories in the United States in the early 1900s were known to have contracted serious radiation poisoning from painting watch dials with radium paint. They were referred to as the ‘radium girls’. Yet, people were drawn to radium like a moth to a flame, and it wasn’t banned until 1968.

In light of the hazardous nature of radium, the search was on for less dangerous substances. Promethium was one option. It is radioactive, but emits only beta particles and has a half-life of less than three years. Seiko were known to have used promethium, but owing to its limited half-life, its glow would fade away rather quickly. Tritium, however, with its low beta emission and a 12.32-year half-life, was a better choice. Tritium was also used by Panerai in their new patented luminescent substance called Luminor, after which their famed Luminor collection is named. The tritium-based Luminor was patented by them in 1949, and its development inspired the now iconic Luminor case design and collection. However, they discontinued the use of tritium itself eventually. In the late 90s, tritium was in fact banned. And tritium-based substances ceased to be used by Omega in 1997, and Rolex in 1998.

Today, tritium is used again by a few manufacturers, however, not as a paint or paste. A radioactive form of hydrogen, tritium gas is filled into borosilicate glass capsules, internally coated with a layer of phosphor. As the gas undergoes beta decay, the electrons released cause the phosphor to glow. The gas is still radioactive, but is apparently less of a hazard than tritium-based paints, because of being in tubes. Luminox and Ball are among the watch manufacturers known to use tritium gas tubes quite prominently on their dials. The advantage is that unlike Super-LumiNova, which will most certainly stop glowing after a few hours of exposure to light, tritium tubes will continue to luminesce, even if the glow becomes dull over the years, and lead to them needing replacement.

The Dawn Of Super-LumiNova

Finally after decades of taking chances with substances that were literally radioactive, there seemed to be some hope that a watch could glow and actually be safe even—imagine that! The idea was to use a phosphor that didn’t require an excitant in order to glow, and would still manage to glow adequately for a prolonged period after exposure to an external source of light. The substance to fill the void created by zinc sulphide’s toxic, co-dependent relationship with radioactive materials was found to be the rather independent strontium aluminate. It was in 1993 when LumiNova was invented by Japan’s Nemoto & Co—who were already in the business of supplying luminous paint to the clock and watch industry since 1941. Strontium aluminate used in LumiNova—along with europium, a safe chemical that aids its phosphorescence—proved to be far more effective than its regressive predecessor, being able to glow several times brighter and longer than zinc sulphide, without causing any harm. The only disadvantage was that the perpetual glow was gone along with the radioactive lumes of the past, but who needs the baggage that came with them anyway!

Eventually, Nemoto partnered with RC-Tritec, a Swiss company, to form LumiNova AG—a Swiss entity that began to produce Super-LumiNova, which is the Swiss version of the same strontium aluminate-based pigment. This is what’s used in most glowing parts in watches today. Over time, there have been customisations to this super pigment by various brands, as they are known to do, creating proprietary versions of existing materials to enhance performance and durability.

Shedding New Light

While Rolex began to use Super-LumiNova in 2000, they introduced their proprietary version of the pigment, called Chromalight in 2008, with the launch of the Oyster Perpetual Sea-Dweller Deepsea. This extreme professional diver’s watch was waterproof down to 3,900m, and imaginably came with luminosity that could even work well at extreme depths. Eventually the maison began to use Chromalight in their other professional watches as well. With its blue glow—as opposed to Super-LumiNova’s more prevalent green—Chromalight lasts for up to eight hours with uniform luminosity. Seiko’s LumiBrite comes with a similar claim, of more intense brightness that lasts for up to five hours in the darkness after being exposed to light.

A blue glow is, however, not restricted to Chromalight. In fact, Super-LumiNova itself is available in different hues, including blue, but is probably not as bright as Chromalight. Green is generally the preferred choice by many watchmakers, owing to the human eye being most sensitive to green emission when shifting from brightness—or photopic vision—into darkness. However, blue is more impactful on the eye in the case of scotopic vision—or vision in extreme darkness, when there is higher sensitivity, but a minimal perception of colour. Sometimes, though, the various hues of Super-LumiNova are used simply for aesthetic purposes. A fine example of that is Breitling’s 2020 SuperOcean Heritage 57, which featured hour markers coated with Super-LumiNova in a rainbow palette of yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet, red, and orange—which are pretty much all the hues that Super-LumiNova comes in. Incidentally, this dial—was in keeping with an ongoing craze of ‘rainbow’ watches—was later presented in a limited edition to help support healthcare workers tackling COVID-19.

Aesthetic uses of Super-LumiNova extend even to the volume of the pigment and its combination with other materials, for larger impact, enhanced luminosity and dimensionality even. For instance, TAG Heuer designed the dials of their 2019 Autavia watches with large Arabic numeral indexes, which were blocks of Super-LumiNova.

On the other hand, H. Moser & Cie. have actually used a custom material called Globolight—a ceramic-based material infused with Super-LumiNova—for the block hands of their Streamliner watches, as well as the large numerals in their Heritage Centre Seconds timepieces. H. Moser even use Super-LumiNova to highlight the unconventional display of time in the Endeavour Flying Hours, with three hour discs coated entirely with the pigment.

Superlative Super-LumiNova

Going a step further in heightening the use of Super-LumiNova, in 2020, Panerai looked back to their pioneering origins in erstwhile forms of luminosity for inspiration, with the Luminor 70th anniversary edition. The latest in their successful efforts towards reclaiming the names Radiomir and Luminor, the Italian brand of Swiss-made watches presented three new special edition Luminors. These watches feature Super-LumiNova not just in the dial markers and hands, but also in an inner bezel, the signature crown protector, the crown itself, and even the stitching on the straps. The latest generation of the pigment used here—the Super-LumiNova X1—provides advanced luminosity, especially noted as being greater than that offered by the tritium-based Luminor.

Of course these extravagant and exciting uses of phosphorescence in watches are possible today because of how safe it actually is to now turn these objets d’art into shiny objects as well. From the long-term ill-effects of radium contamination and poisoning that has probably impacted people’s health in ways we’ll never truly know, to revelling in the thrill of these fascinating glowing timepieces—watchmaking has certainly come a long way.

I appreciate the distinctions you’ve highlighted within this post.

It adds coatings of understanding to the topic.

I like what all u have written. This all helped me for getting knowledge about the watches.