ExclusiveA Day With Parmigiani: Our Visit To Their Manufacture

With manufacturing facilities in various parts of Switzerland, Parmigiani is one of the few watchmakers with the capability to manufacture everything in-house, which is rather impressive for a brand that’s been around for less than 25 years. We took a trip to their manufacture units in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and around the brand’s hometown, Fleurier, including the headquarters

May We Recommend

Walking through the various specialised manufacturing facilities of Parmigiani, one would hardly think of the brand as being a relatively new player in the Swiss watch industry. Each piece of equipment, every tool, every employee and watchmaker has a well-defined and dedicated purpose. As we tour the various units of the Parmigiani manufacture and see the individuals polishing cases, decorating components, and assembling movements, all we notice are focus, dedication and passion for the art of watchmaking.

The Outer Build

It’s always fascinating to see something created out of nothing, especially when it’s something as exquisite as a fine timepiece. The experience starts for us at Les Artisans Boîtiers in La Chaux-de-Fonds, where we’re introduced to Léa Parmigiani. The daughter of the brand’s founder Michel Parmigiani, Léa is currently pursuing an apprenticeship with the company. She joins us on our tour, offering insights into the phenomenon that her father created.

Les Artisans Boîtiers, or LAB, is where the build of each Parmigiani watch—the case—is created. Treating the metal and preparing it for the construction of the cases turns out to be an exhaustive process in itself, but it’s only the beginning. As we move on from the large barrels of machinery where the metals are washed and treated with chemicals. We move through various other sections, as we see people developing technical drawings on high-tech software, while 3D printouts of case designs lie around for pre-production review. As we move along, we notice the actual parts of watch cases waiting to be welded, and we spot the framework of a Bugatti Type 390 case among a few samples. The instantly identifiable shape isn’t the only one we recognised. Where the cases are polished to the desired perfection, we see the signature Kalpa case, with their external lugs. The selection of filing material used depends on the finish desired. As you go from matte and brushed to glossy and polished, the materials go from coarse to fine. At each step, we see digital Vernier calipers being used to measure the widths and heights of each part, as they understandably can’t afford to be inconsistent with sizes.

The LAB unit has about 40 employees and they are equipped with the capability to manufacture cases and loops, taking into consideration the complexity of the finer details and the materials used. It’s not as technical as the calibre making per se, but getting the cases right ensures that the calibres are protected well enough to do what they’re supposed to do.

Faces In Creation

The next stop we make is in the Quadrance Habillage, where all kinds of dials are created. One might think that they’re merely discs or plates on which markers are printed or applied. That might be true for a certain kind of dial, but we know that when it comes to watches from the likes of Parmigiani, it’s not always that simple. Whether it’s a subtle finish or minor detail, the nuance added to a dial works wonders for its overall impact. In fact, treating a dial to look as perfect as it could be is paramount, because that’s what you instinctively look at first when you behold a watch, before you notice the case or the brand, or even comprehend the position of the hands to read the time. We see that achieving the right hue desired for a particular dial—be it chocolate, aubergine or slate grey—and making the best possible pigment to give it an even and refined finish is crucial. Consider a guilloché -finished dial and that goes to another level. And make that a mother-of-pearl dial and then it’s far from being a simple little disc. We see a craftswoman engrossed in an aventurine glass dial of what looks like a Tonda Metropolitaine model. As she finishes the piece, gingerly applying the markers, she’s practically oblivious to our presence. And I suppose that’s how they need to be—completely in that zone.

The Heart Of A Watch

With the La Chaux-de-Fonds part of our tour over, we head next towards Fleurier, which is about a 40- to 45-minute drive away. Before we head to the headquarters, we stop at the facility where the movements are put together and the watches are assembled. Called the Vaucher Manufacture Fleurier (VMF), this manufacturing establishment is equipped to create all the major components of the movements, with only hairsprings and the tinier parts made in another facility located somewhere between the towns of Neuchâtel and Basel. Established in 2009, VMF is partly owned by Hermès, the manufacturers of luxury leather goods, scarves, high-end watches and several other products. As most leather straps used in Parmigiani watches are made by Hermès, sharing this facility works wonderfully for the brands. In fact, VMF also works with a lot of smaller companies. We’re told that anyone looking to outsource movement manufacturing can approach them.

We first enter the development section, where a lot of the research takes place, as movements are virtually constructed to scale on computer software. We see a scaled-up model of the movement used in a Tonda chronograph limited edition, complete with the gear trains and bridges. It almost looks like a toy, but as we see the skilled engineers at work, it’s clear that it takes a lot for any movement to even get to that stage. And then considering that in 22 years, Parmigiani has created 32 in-house calibres definitely has us in awe of what they do here. Once these constructions are to their liking, these models are developed as prototypes in metal.

From Metal To Mechanism

Simplistically put, to create a movement, you need a mainplate on which everything is mounted. This ‘motherboard’—so to speak—is cut and treated in machines similar to those used in LAB, but far more refined. A simple metal plate goes through the machine, through all the containers, with tools and parts working on it automatically, resulting in refined mainplates almost ready to build on. Also used to make the bridges that hold components together, these machines can work with German silver and other materials, including the widely used brass. Once ready, brass mainplates are stored in humidity-controlled storage units that prevent oxidisation.

The next section we see is where metal is cut. From fine metallic sheets cut by laser to make the tiniest appliques, to heavy-duty machines used to impression more solid chunks of metal, there’s a lot going on here. It’s probably the most industrial department we’ve seen so far. Yet, some parts made here—including text characters of logos and typography to be applied on dials—are so fine that they need to be handled with tools that have tips as fine as hair strands. Finer than those tools are the metallic threads used to slice through heavy tungsten blocks, to create not just components, but other watchmaking tools as well. They’re actually able to make their own tools!

The Finer Details

When watches have skeleton displays or even transparent casebacks, it’s as important to make the components look pretty as it is to impress any beholder with the mechanics. We see how this is done in the component decoration department, where we see more craftswomen and craftsmen thoroughly engaged with the components on their workbenches. Here we see the Côtes de Genève parallel lines, soleillage intersecting lines, and the perlage overlapping circles being etched onto the mainplates and bridges. One part has to be finished in one sitting so as to ensure that the pattern continuity isn’t lost, and precise measurements are maintained. Yes, they use machines, but without being perfectly initiated by hand, it would all just be a mess. We even see some anglage work being done. The smoothening or bevelling of a bridge, anglage just adds to the nuance of the mechanical beauty that is the calibre it is used in.

The Finishing Touch

Before heading to see the assembly of movements, we drop in to say hello to the apprentices. A bunch of youngsters, mostly with no prior knowledge of watchmaking, these people embark upon a four-year apprenticeship programme. They start with learning how to build their tools, and end with a complete project and certifications as official qualified watchmakers. Some of them go on to work for Parmigiani, while all of them are encouraged to seek employment elsewhere, for a more well-rounded development of their craft.

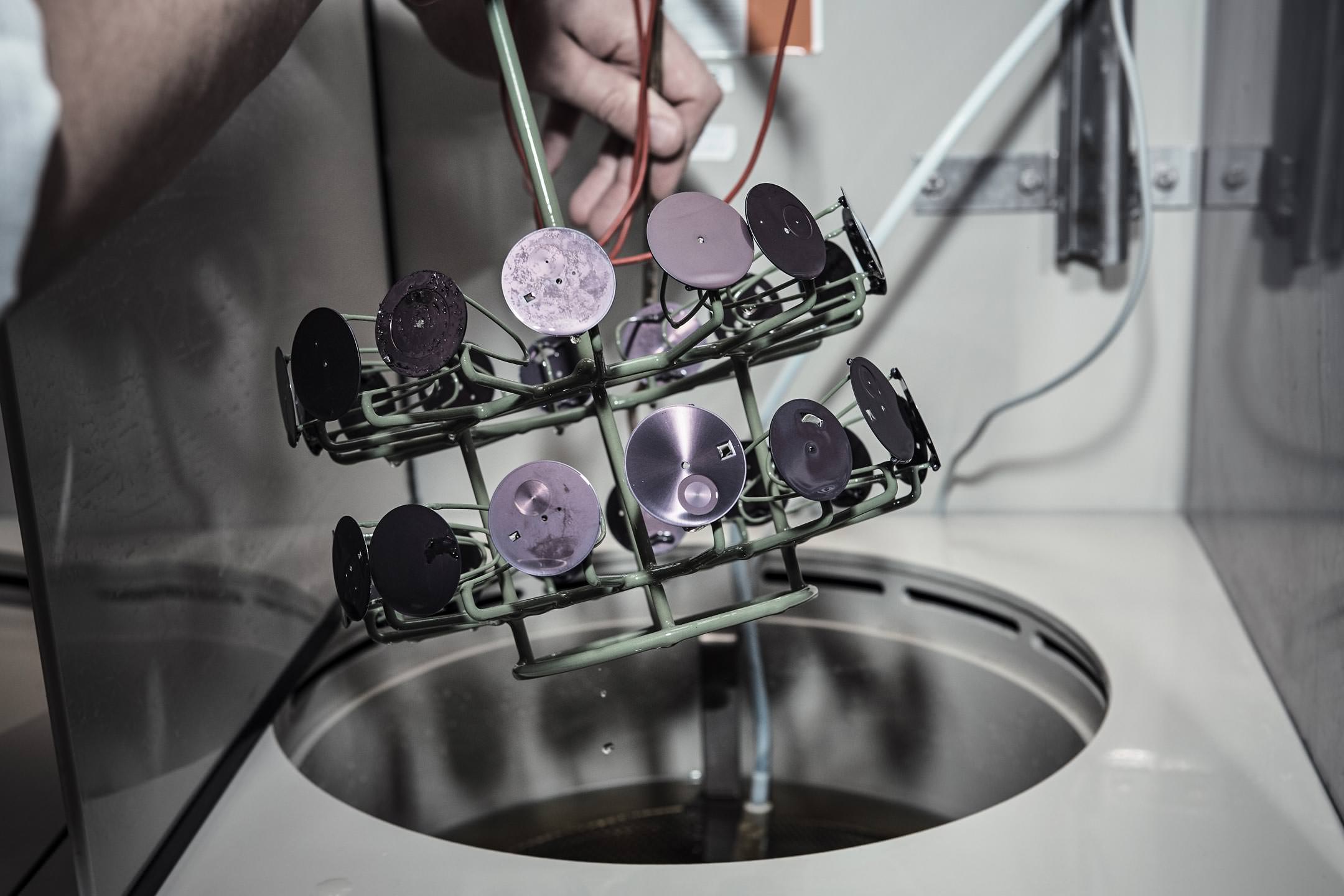

We see more skilful hands in the assembly room, with an assembly line for baseline calibres. The complication movements are done individually. And finally, we see the movements being introduced into the cases, finished with the crown insertion, the hands, the gaskets, casebacks and so on. We’re told that grand complication watches are assembled by a select few in headquarters itself. The functioning watches assembled and sealed are put in a machine to perform all kinds of tests including water resistance. The watch is taken through the sections of the large machine, over hours and sometimes days, and it’s all automated, so that the tests can be carried out after working hours and even over the weekends. And then the watches are ready for those Hermès straps to be fitted, unless they have metal bracelets, and then protectively packed and kept ready to be shipped out.

A Throwback Finale

Our last stop was the headquarters in Fleurier, where we took a peek into the restoration wing. Before the brand was launched in 1996, Michel Parmigiani was a restorer of antique watches and clocks. We’re told that his atelier has even been responsible for restoring several pieces seen in the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva. It was his work in restoring pieces from the Sandoz family collection that gave him the push to start his own brand, which the Sandoz Foundation encouraged and even invested in. The restoration work continues, we see, as the skilled craftsmen there take immense pride in what they literally bring to the table. Making unique pieces work—such as an ornate pocket knife clock with a specialised minute repeater movement—is clearly a fascinating and rewarding experience for them. We see a piece that the new Parmigiani Capitole watch was inspired by and we’re told that this wing is also a source of inspiration for the brand’s contemporary collections. Developing modern wristwatch movements based on antique pocket watches is difficult as it involves making them tougher to sustain the shock and mobility that wristwatches have to face.

Saving the best for the end, the last thing we see before our day with Parmigiani ends, is an antique tobacco box, which is not about storing tobacco. It does have a small chamber for tobacco, but it’s primarily an automaton—a mechanical device that works on the same principles as those of mechanical watchmaking. When wound and opened, out pops an intricately crafted bird that sings and does a little dance, with wings flapping, head rotating and beak moving to the melody. After the little performance, it promptly goes back in as the lid shuts on its own.

With that, our day with Parmigiani ends. The fascinating journey of a Parmigiani watch doesn’t end there though. While every department works like a well-oiled machine, the talent, skill and the human touch create products that are bound to elicit from any wearer an emotional reaction that could last a lifetime.