FeatureWhat Are In-House Movements And Should You Care? An Expert Guide

In-house or outsourced? When it comes to watch movements, the answer isn't as clear-cut as you might think

May We Recommend

The term ‘in-house movement’ gets tossed around like a badge of honour in watch circles, but does it really mean what we think it means? For years, watch enthusiasts have clamoured for timepieces with movements made under one roof, often equating ‘in-house’ with superior quality and craftsmanship. But the reality, as with many things in the world of fine watchmaking, is far more nuanced.

Historically, the Swiss watch industry thrived on collaboration, with specialists focusing on different components. Fast forward to today, and the landscape has shifted dramatically. As we find ourselves in an era where mechanical watches are more luxury than necessity, the notion of ‘in-house’ has been reinvented, repackaged, and sometimes, frankly, misrepresented. ‘In-house’ has become a marketing buzzword, with brands scrambling to claim this coveted status. But rarely do we pause to ask: what does this really mean, and more importantly, should we care?

In this article, we’ll explore the rise of in-house movements, what the term really means, and whether it should be a deciding factor in your next watch purchase. Along the way, we’ll showcase and examine various timepieces that boast in-house calibres, offering a closer look at some of the industry’s most talked-about movements. By the end, you’ll have a clearer picture of the complex ecosystem that powers the watches we love and perhaps a new perspective on what really matters when you’re choosing your next timepiece.

The Rise Of In-House Movements

The shift towards in-house movements didn’t happen overnight. It was a gradual transformation, driven by a combination of necessity and marketing savvy.

Traditionally, the Swiss watch industry operated on a model known as établissage—a collaborative system where specialised firms each contributed their expertise to the final product. This approach allowed for a rich ecosystem of innovation and craftsmanship, with brands focusing on design, assembly, and marketing while relying on dedicated movement makers for the hearts of their timepieces.

However, the landscape began to shift in the early 2000s. The Swatch Group, which owned ETA—the industry’s primary supplier of movements—announced plans to reduce the supply of ébauches to competitors. This move sent shockwaves through the industry, prompting many brands to reconsider their reliance on external suppliers.

Simultaneously, the luxury watch market was evolving. As mechanical watches transitioned from practical timekeepers to symbols of prestige, brands sought ways to differentiate themselves. In-house movements became a compelling narrative—a story of independence, expertise, and exclusivity that resonated with consumers increasingly interested in the provenance of their purchases.

The result? A surge in brands claiming in-house capabilities, each vying to showcase their horological prowess.

What Makes A Movement Truly ‘In-House’?

Defining an in-house movement should be simple, but in the world of horlogerie, few things are. At its purest, an in-house movement is one entirely designed, developed, and manufactured under one roof. Every component, from the base plate to the balance spring, is produced by the brand whose name adorns the dial.

In reality, the term inhabits a spectrum. At one end, you have the true manufactures—brands like Rolex, Jaeger-LeCoultre, or Seiko, who control nearly every aspect of production. On the other, you find brands that heavily modify base movements from external suppliers, adding their own bridges, rotors, or complications.

Between these extremes lies a grey area where the definition of ‘in-house’ becomes murky. Some brands tout movements as in-house when they’re designed internally but manufactured by a sister company or third-party supplier. Others may use ‘manufacture calibre’ to describe movements made exclusively for them, even if they didn’t design them.

This ambiguity has led to controversies. TAG Heuer faced backlash when its touted ‘in-house’ Calibre 1887 was revealed to be based on a Seiko design. Bremont encountered similar scrutiny over its BWC/01 movement. These instances highlight the industry’s struggle with transparency and the malleability of the ‘in-house’ definition.

The debate extends to conglomerate-owned brands. When Richemont Group brands like IWC or Panerai use movements from the group’s ValFleurier facility, are they truly ‘in-house’? The answer often depends on who you ask.

In this landscape of varying definitions and marketing spin, one thing becomes clear: the term ‘in-house’ alone is insufficient to gauge a movement’s quality or a watch’s value. As enthusiasts, we must look beyond the buzzwords to truly understand what ticks beneath the dial.

The Pros Of In-House Movements

While the term ‘in-house movement’ has certainly been overused in marketing, there are legitimate advantages to this approach that deserve consideration. When a watch brand truly develops and manufactures its own movements, it opens up a world of possibilities that can benefit both the company and the consumer.

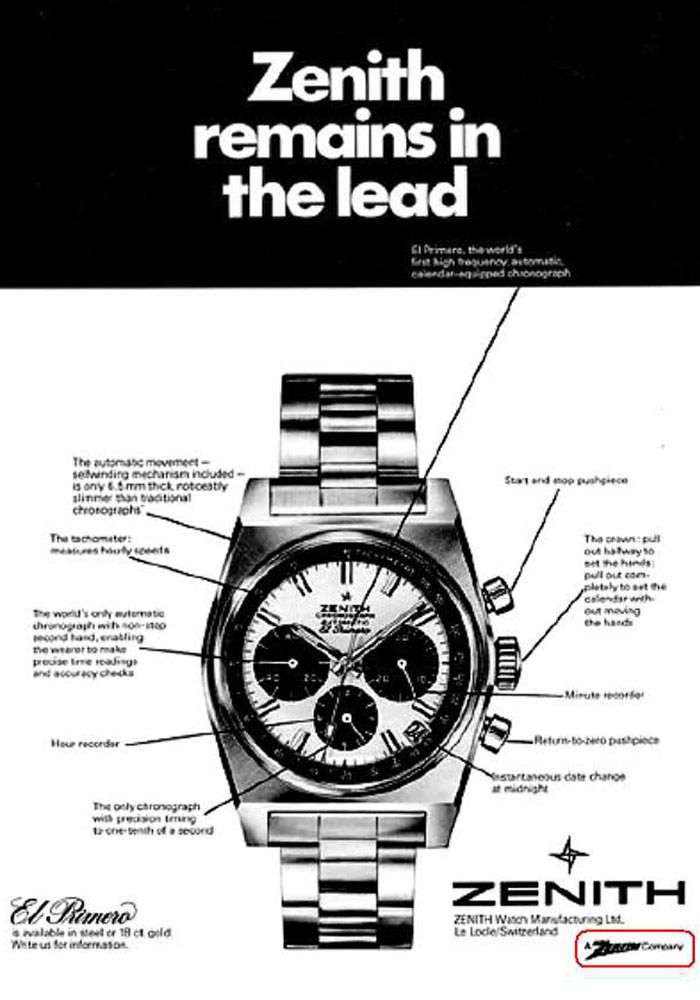

First and foremost, in-house production gives a brand complete control over design and engineering. This freedom allows watchmakers to tailor movements specifically to their cases and complications, potentially resulting in more cohesive and innovative timepieces. Take, for example, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s ultra-thin movements or Zenith’s high-frequency El Primero calibre. These achievements might not have been possible without the brands’ ability to experiment and iterate in-house.

Moreover, vertical integration can foster innovation. When a brand invests in its own movement production, it often leads to the development of new materials, techniques, and complications. Brands like Omega and Rolex have leveraged their in-house capabilities to push the boundaries of anti-magnetic properties and chronometric precision, respectively.

As watch enthusiasts, we simply can’t ignore the romantic appeal of a fully-integrated watchmaking process. There’s something undeniably compelling about a timepiece where every component, from the balance wheel to the escapement, was conceived and crafted under one roof. This holistic approach to watchmaking can result in a level of coherence and attention to detail that’s difficult to achieve otherwise.

Lastly, there’s the question of exclusivity. A well-executed in-house movement can become a brand’s signature, a unique selling point that sets it apart in a crowded market. Think of Omega’s Co-Axial escapement or Rolex’s perpetual rotor—technical features that have become inextricably linked with their respective brands.

The Cons And Criticisms

However, the pursuit of in-house movements isn’t without its drawbacks. The most obvious is cost. Developing and producing movements requires significant investment in research, equipment, and skilled labor. These costs inevitably trickle down to the consumer, often resulting in higher price tags.

Reliability can also be a concern, particularly with newly-developed calibres. While established third-party movements have often been refined over decades, new in-house creations may suffer from teething problems. The Tudor GMT’s date-change issue or the early problems with IWC’s 52000 series serve as cautionary tales.

Servicing presents another potential hurdle. Proprietary components and specialised designs can make repairs more complex and expensive. In some cases, watches may need to be sent back to the manufacturer for service, leading to longer wait times and higher costs.

There’s also the question of necessity. Does every watch really need a bespoke engine? For many timepieces, particularly in the entry-level luxury segment, a well-regulated third-party movement might offer better value and reliability than a less refined in-house alternative.

Third-Party Movements: The Unsung Heroes

While in-house movements grab headlines, it’s worth remembering that some of the most revered watches in history have relied on third-party calibres. The Patek Philippe ref. 5970 perpetual calendar chronograph, powered by a Lemania-based movement, is a prime example of how external movements can be elevated to extraordinary heights.

Third-party movements, particularly those from established makers like ETA, Sellita, or Soprod, offer several advantages. Their reliability and accuracy have been proven over millions of units and decades of use. They’re often easier and less expensive to service, ensuring your timepiece can be kept running smoothly for generations.

These movements also allow brands to focus their resources on other aspects of watchmaking. Case design, dial execution, and overall finish can be prioritised without the enormous overhead of movement production. This approach has given rise to numerous successful brands, from micro-independents to established luxury houses.

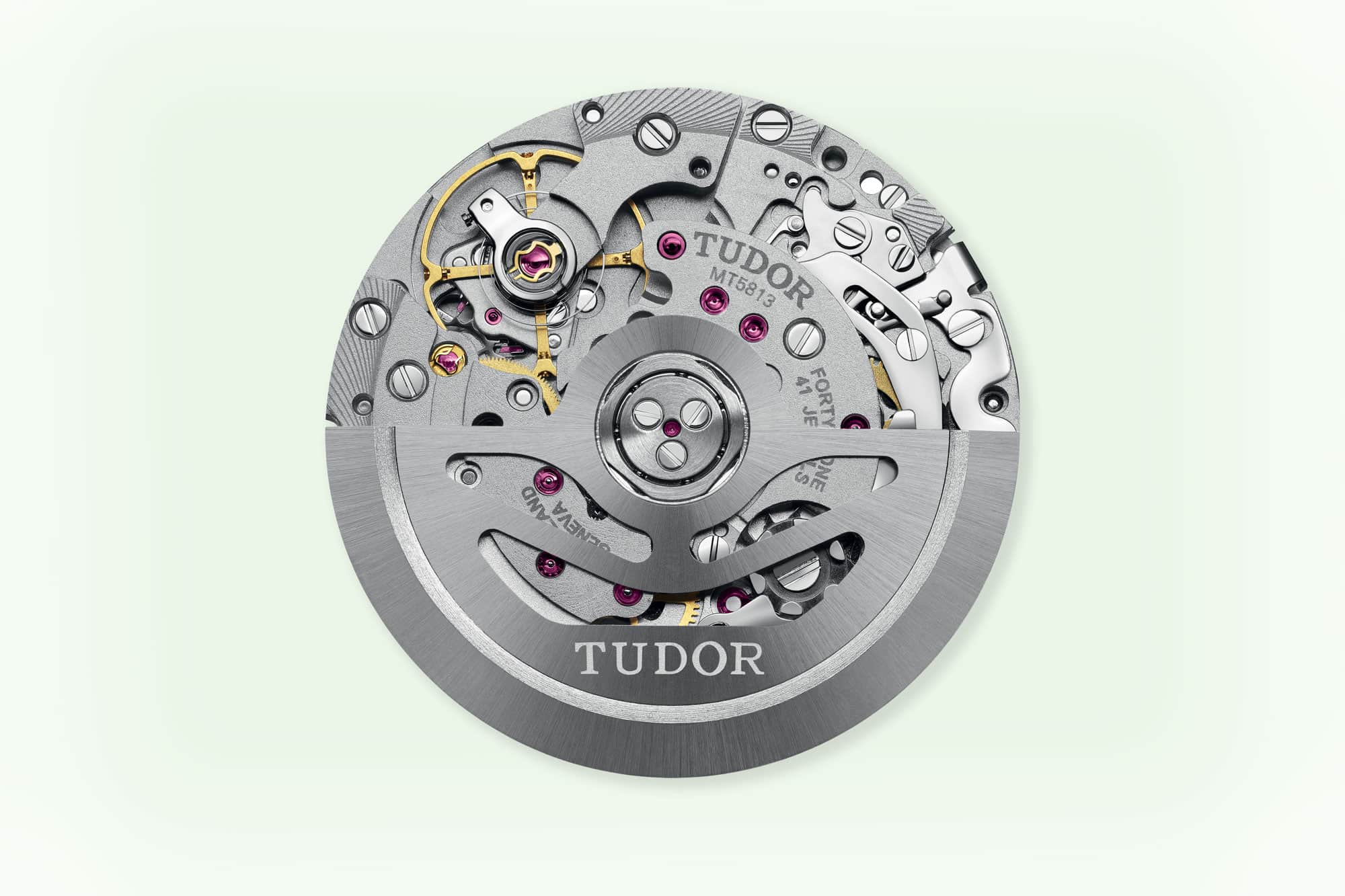

Moreover, the use of third-party movements doesn’t preclude innovation. Many brands modify base calibres extensively, adding complications or improving performance. Tudor’s collaboration with Breitling, resulting in the MT5813 chronograph movement, demonstrates how shared expertise can lead to impressive results.

In the end, the choice between in-house and third-party movements isn’t a simple matter of superior versus inferior. Each approach has its merits, and the real measure of a movement’s worth lies in its performance, reliability, and the overall value it brings to the timepiece, not just its origin.

Final Thoughts

As we’ve explored, the world of in-house movements is far more complex than marketing slogans might suggest. These bespoke calibres can represent the pinnacle of a brand’s horological expertise, offering unique features and a deep connection to watchmaking heritage. Yet, they’re not the only path to horological excellence.

The future of watchmaking likely lies not in a rigid dichotomy between in-house and third-party movements, but in a nuanced ecosystem where innovation thrives in various forms. We’re already seeing brands collaborate in unexpected ways, pooling resources and expertise to push the boundaries of what’s possible in a watch movement. This evolution promises exciting developments for watch enthusiasts, regardless of where the calibres originate.

Ultimately, the ‘in-house versus third-party’ debate is just one facet of what makes a timepiece truly special. Your decision needs to be guided by a holistic appreciation of the timepiece, not just buzzwords. Consider its design, its functionality, its history, and yes, its movement—but also how it speaks to you personally.