FeatureSound Of The Heartbeat: A Guide To Your Mechanical Watch’s Frequency

The frequency of a movement plays a crucial role in determining the accuracy and power reserve of a timepiece. In the past few decades, several watchmakers have pushed the boundaries of engineering and innovation to achieve faster-beating movements for better performance and top-notch precision. Let’s delve deeper to understand how frequency impacts a watch’s functionality, and its evolution over the years

May We Recommend

While buying a mechanical watch, one might overlook the frequency of the movement inside, compared to more pertinent aspects like complications, case size, and dial design. However, there is a deep relationship between the rate at which a watch ticks, its accuracy and power reserve. Today, in the horological industry, the frequency of a movement has become a real asset and several watchmakers are competing with each other to craft timepieces with higher oscillation speed—a hallmark of better performance. While most of the watches available in the market usually beat at 21,600vph (3Hz) or 28,800vph (4Hz), there are some high-end timekeepers with a whopping frequency of up to 72,000vph (10Hz). But before we take a look at them, let’s first understand what frequency actually means, its transformation with regard to haute horlogerie over the years, and its impact on a watch’s precision and performance.

What Is Frequency

A mechanical watch movement consists of a power source—also called the mainspring, transmission or the gear train, and a regulation system comprising the escapement, balance wheel, and hairspring. The power flows from the mainspring, via transmission, to the escape wheel, and it is through the oscillations or vibrations of the balance wheel that the power is ultimately and accurately dissipated and the movement’s frequency is manifested.

Frequency is expressed in vibrations per hour (vph) or Hertz (Hz), a unit named after Heinrich Hertz who was the first man to give a substantial proof of the existence of electromagnetic waves, and it is determined by the number of oscillations that the balance wheel makes in a single second. So, for example, if a timepiece ticks at 4Hz or 28,800vph, it means the balance wheel is operating at four oscillations per second or eight vibrations per second. In other words, half oscillation or one vibration is counted when the balance wheel moves in a single direction, and one oscillation is counted when the balance wheel has moved and returned to its original position—just like a seesaw. Therefore, the bigger the number of Hz or vph, the faster the balance vibrates or oscillates.

Evolution Of Frequency

High-frequency timekeepers have always been part of the horological industry and their history can be traced back to the 19th century. In 1815, legendary watchmaker Louis Moinet designed the world’s first chronograph, which he named Compteur de Tierces and it ran at a mind-boggling speed of 30Hz. No wonder, even today Moinet is considered the father of high-frequency timekeeping.

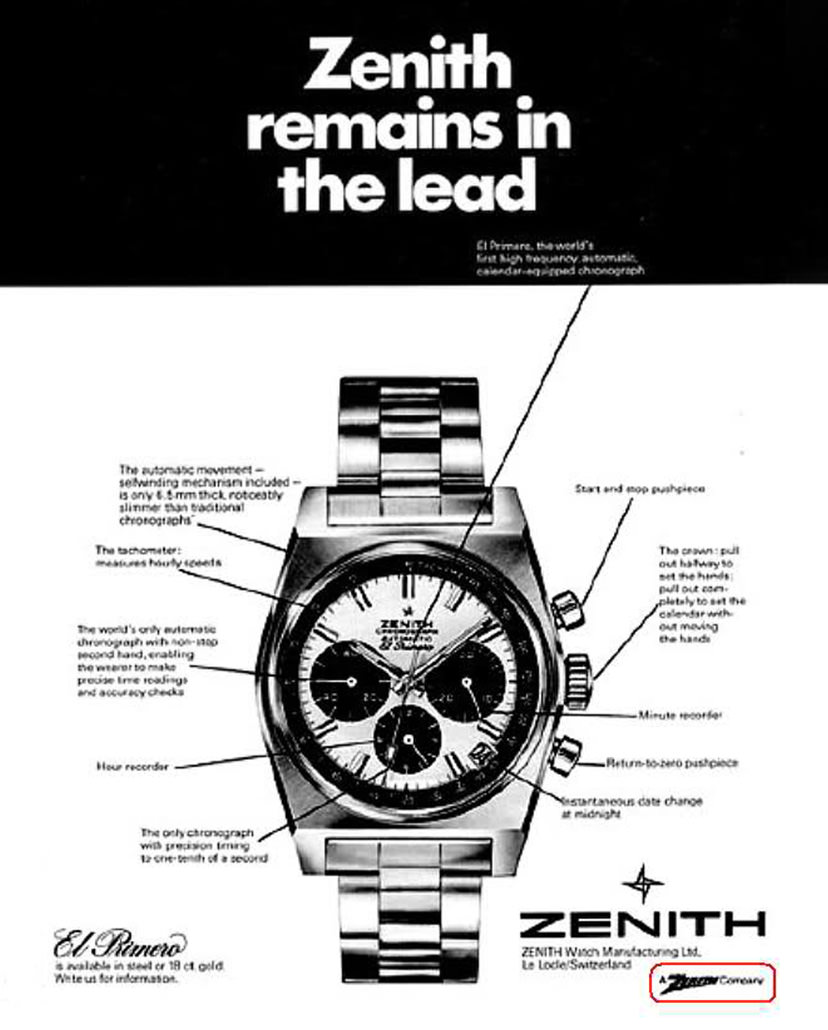

However, for the longest time, the average speed at which most of the watches ran was 18,000vph or 2.5Hz. But things started changing during the 1960s and 1970s with the launch of Seiko’s Hi-Beat series with the movement beating at 21,600vph, and Heuer-Breitling-Hamilton-developed Calibre 11—offering a beat rate of 19,800vph. Though, the real impetus came in 1969, with the introduction of Zenith’s El Primero calibre, which sent shock waves across the watchmaking industry.

The El Primero wasn’t just a high-frequency movement—apart from beating at the rate of 36,000vph, it was also the first self-winding chronograph to be released. Offering supreme accuracy, a power reserve of 50 hours, and a sleek profile (its height was just 6.5mm), the calibre instantly became a hit and catapulted to the pinnacle of fame and glory. However, even after such ingenious inventions, it was a rarity to witness timepieces equipped with high-beat movements. In the last few decades, this has radically transformed and the market is now flooded with watches that offer a frequency of 21,600vph or 28,800vph, and much higher. What Seiko labelled as ‘Hi-Beat’ has become mainstream and the standard frequency available. The foremost reason for this change? The accuracy.

Frequency, Accuracy, And Performance

It’s generally believed that a higher frequency can improve the potential precision of the watch as a balance wheel beating at a higher rate is more stable and gets less influenced by external factors like temperature, magnetic fields, or external shocks. Not only this, a faster movement recovers from disturbances more quickly than the slower ones and offers a more stable timekeeping system. Also, the high-beat movements aren’t just limited to watches without any complications. They are the first choice for powering chronographs as their faster frequency allows for more precise measurement of timing intervals. However, such movements come with baggage. They not only consume more power but are also more prone to wear and tear, which leads to shorter service intervals and costly replacements—a headache for both the manufacturer and buyer.

This is one of the reasons why many brands don’t prefer a movement running above 4Hz. For example, Rolex began using Zenith’s El Primero in the 1980s but modified it to reduce its frequency to 4Hz from the original 5Hz. Till date, no Rolex watch offers a higher frequency than 4Hz. Other watchmakers who haven’t embraced faster frequencies are Omega. Their 2019 released Calibre 3861—powers the iconic Speedmaster models, and beats at just 21,600vph but provides an impressive power reserve of 50 hours, which is more than its predecessors.

The Advent Of New Technology

What liberated the horological industry from most of the aforementioned woes due to high frequency was the introduction of silicon. In 2001, avant-garde watchmaker, Ulysse Nardin launched their revolutionary Freak model that used silicon for two escapement wheels instead of the usual steel. Since then, the silky material became a go-to choice for watchmakers since it’s anti-magnetic, lighter and harder than steel, and operates without oil. Therefore, the use of silicon translates to a lower requirement when it comes to servicing and an increase in the longevity of the watch. Following in the footsteps of Ulysse Nardin, Breguet also began to incorporate silicon in their timepieces with the launch of Classique Chronométrie 7727 in 2011—the first non-chronograph watch that could oscillate at a frequency of 10Hz or 72,000vph. A year later, Chopard presented their L.U.C 8HF that used silicon for certain escapement components, including the escape wheel and offered a beat rate of 56,000vph. But among these brands, there was one watch manufacturer—TAG Heuer that took an entirely different approach and took their frequency game to the next level.

In 2012, they unveiled the Mikrogirder 2000, a concept watch that redefined high-beat movements with a freakishly fast frequency of 1,000Hz. To achieve this milestone, the engineering team of the brand ditched the conventional balance wheel and spiral hairspring system, and instead opted for a completely new regulator system, consisting of a linear oscillator—vibrating at a very small angle in comparison to the traditional mechanism. This allowed the movement to run at an ultra-high speed (250 times faster than an average watch) along with an accuracy of 5/10,000th of a second. Nothing short of a technical marvel, the Mikrogirder 2000 not only exhibited cutting-edge technology but it also paved the way for the watches of tomorrow.

Onward And Upward

Over the years, more and more watch manufacturers have gravitated towards equipping their timepieces with faster beating movements. A higher frequency is not just a reflection of higher accuracy. It serves as a canvas for watchmakers to showcase their ingenious craftsmanship, innovation and engineering skills. With the discovery of new materials and the invention of new mechanisms, the search for even faster frequencies is far from getting over, and it’s heartening to witness that in a world dominated by smartwatches and quartz movements, something as traditional and age-old as gears and levers can also be pushed to unimaginable limits.